|

[3 min read, open as pdf ]

Central Banks' policy rates are expected to pivot towards cuts in 2024 with a material impact on asset class perspectives.

Read the full article in FT Adviser Wealth Manager's Ross Miller chats to Elston Consulting's Henry Cobbe. They discuss the return of yield and how it plays out across equities, bonds and alternatives.

Listen to the podcast [5min read, open as pdf]

[3 min read, open as pdf]

[3 min read, open as pdf]

Through the looking glass: a curiouser new paradigm Traditionally you bought bonds for income, and equity for risk. Ironically, now it’s the other way round. Read the full article Watch the CPD webinar: Diversifying income risk Find out more [3 min read, open as pdf]

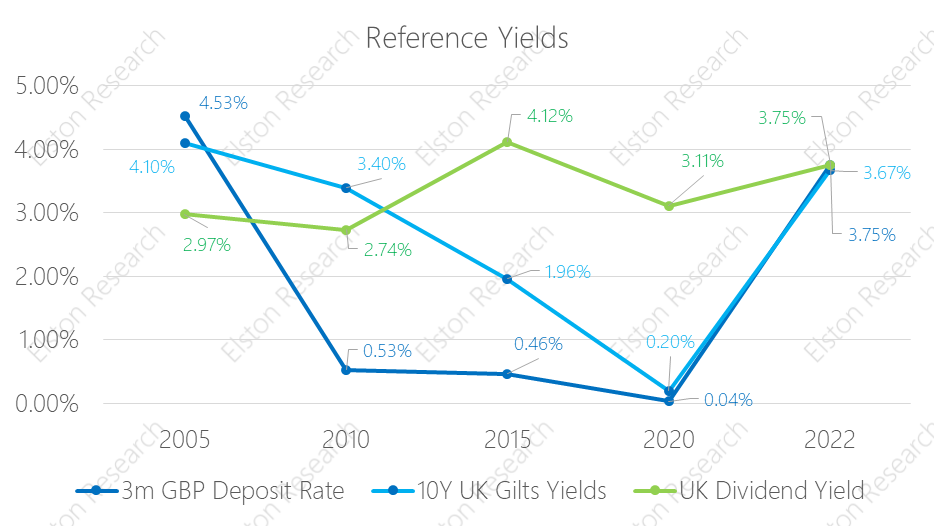

2021 in review Our 2021 market roundup summarises another strong year for markets in almost all asset classes except for Bonds which remain under pressure as interest rates are expected to rise and inflation ticks up. Listed private equity (shares in private equity managers) performed best at +43.08%yy in GBP terms. US was the best performing region at +30.06%. Real asset exposures, such as Water, Commodities and Timber continued to rally in face of rising inflation risk, returning +32.81%, +28.22% and +17.66% respectively. 2022 outlook We are continuing in this “curiouser, through-the-looking glass” world. Traditionally you bought bonds for income, and equity for risk. Now it’s the other way round. Only equities provide income yields that have the potential to keep ahead of inflation. Bonds carry increasing risk of loss in real terms as inflation and interest rates rise. Real yields, which are bond yields less the inflation rate, are negative making traditional Bonds which aren’t linked to inflation highly unattractive. Bonds that are linked to inflation are highly sensitive to rising interest rates (called duration risk), so are not attractive either. How to navigate markets in this context? The big three themes for the year ahead are, in our view:

See full report in pdf Attend our 2022 Outlook webinar [3 min read, open as pdf]

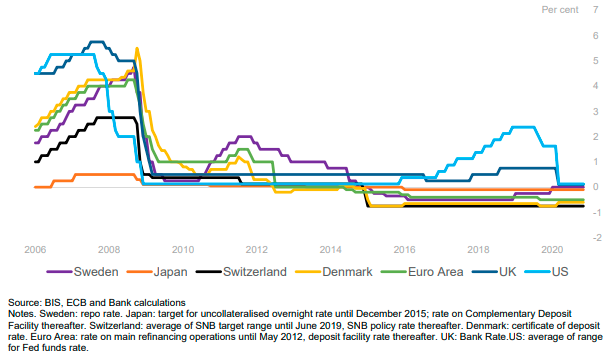

A “last resort” policy tool Zero & Negative Interest Rate Policy are Non-Traditional forms of Monetary Policy is a way of Central banks creating a disincentive for banks to hoard capital and get money flowing. Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) is when Central Banks set their “policy rate” (a target short-term interest rate such as the Fed Funds rate of the Bank of England Base Rate) at, or close to, zero. ZIRP was initiated by Japan in 1999 to combat deflation and stimulate economic recovery after two decades of weak economic growth. Negative Interest Rate Policy (NIRP) is when Central Banks set their policy rate below zero. Japan, Euro Area, Denmark, Sweden are currently using a NIRP. US & UK are currently using a ZIRP, and are considering a NIRP. Fig.1. Advanced economy policy rates Whilst bond prices may imply negative real yield, or negative nominal yields, a NIRP impacts the rates at which the Central Bank interact with the wholesale banking system and is intended to stimulate economic activity by disincentivising banks to hold cash and get money moving. A NIRP could translate to negative wholesale rates between banks, and negative interest rates on large cash deposits, but not necessarily retail lending rates (e.g. mortgages).

Ready, steady, NIRP Negative Interest Rates were used in the 1970s by Switzerland as an intervention to dampen currency appreciation. . It was the subject of academic studies and was seen as a last resort Non-Traditional Monetary policy during the Financial Crisis of 2008 and during the COVID crisis of 2020. Sweden adopted NIRP in 2009, Denmark in 2012, and Japan & Eurozone in 2014. The Fed started looking closely at NIRP in 2016. According Bank of England MPC minutes of 3rd March 2021, wholesale markets are generally prepared for negative interest rates as have already been operating in a negative yield environment. By contrast, retail banks may need more time to prepare for negative interest rates to consider aspect such as variable mortgage rates. There are arguments for and against NIRP. The main argument for is that NIRP is stimulatory. The main argument against is that NIRP failed to address stagnation and deflation in Japan and can create a “liquidity trap” where corporates hoard capital rather than spend and invest. The hunt for yield With negative interest rates, there will be an even greater hunt for yield. We look at the some of the options that advisers might be invited to consider.

Getting the balance right between additional non-negative income yield and additional downside risk will be key for investors and their advisers when preparing for and reacting to a NIRP environment. [5 minute read, open as pdf] Sign up for our upcoming CPD webinar on diversifying income risk Summary

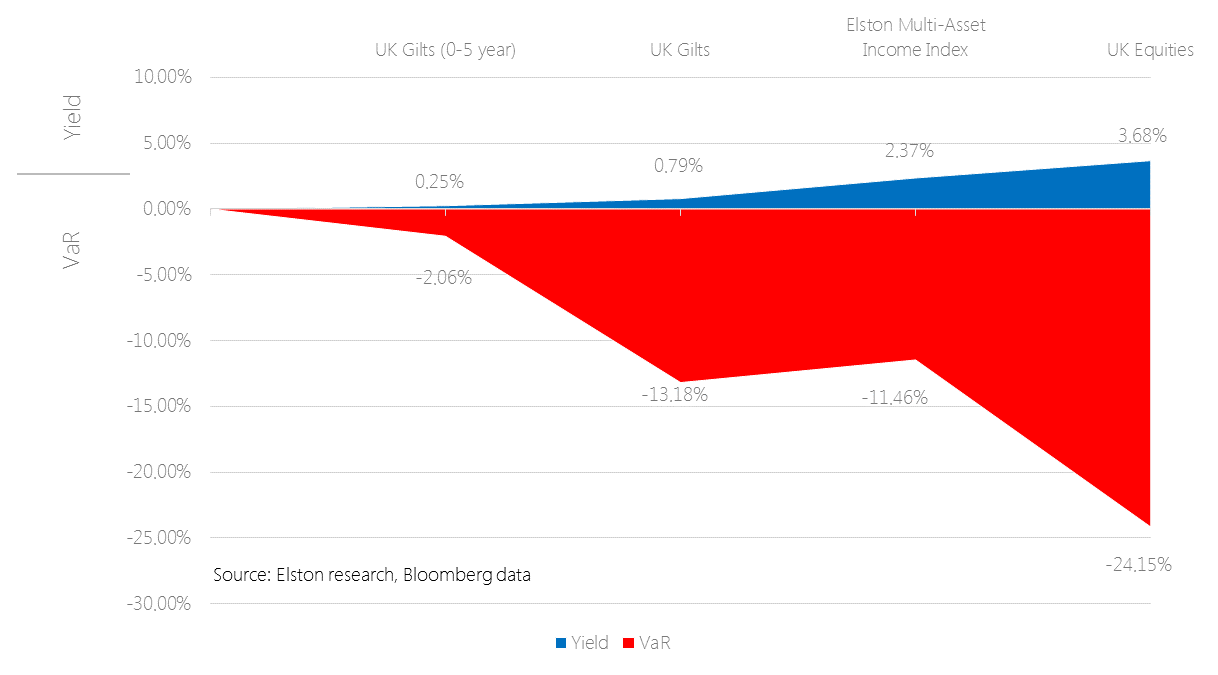

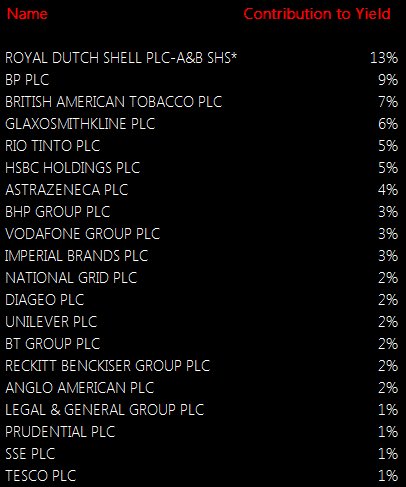

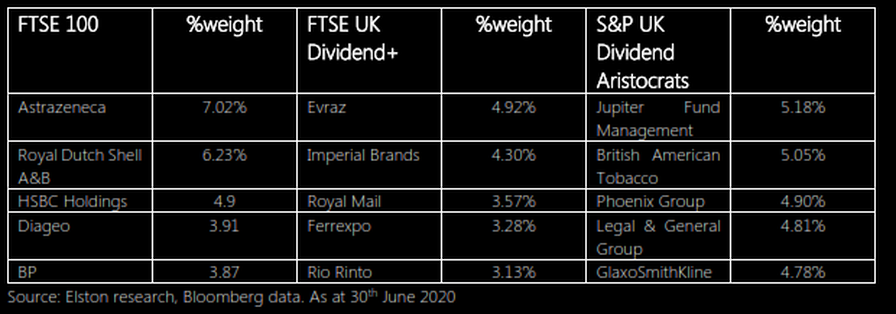

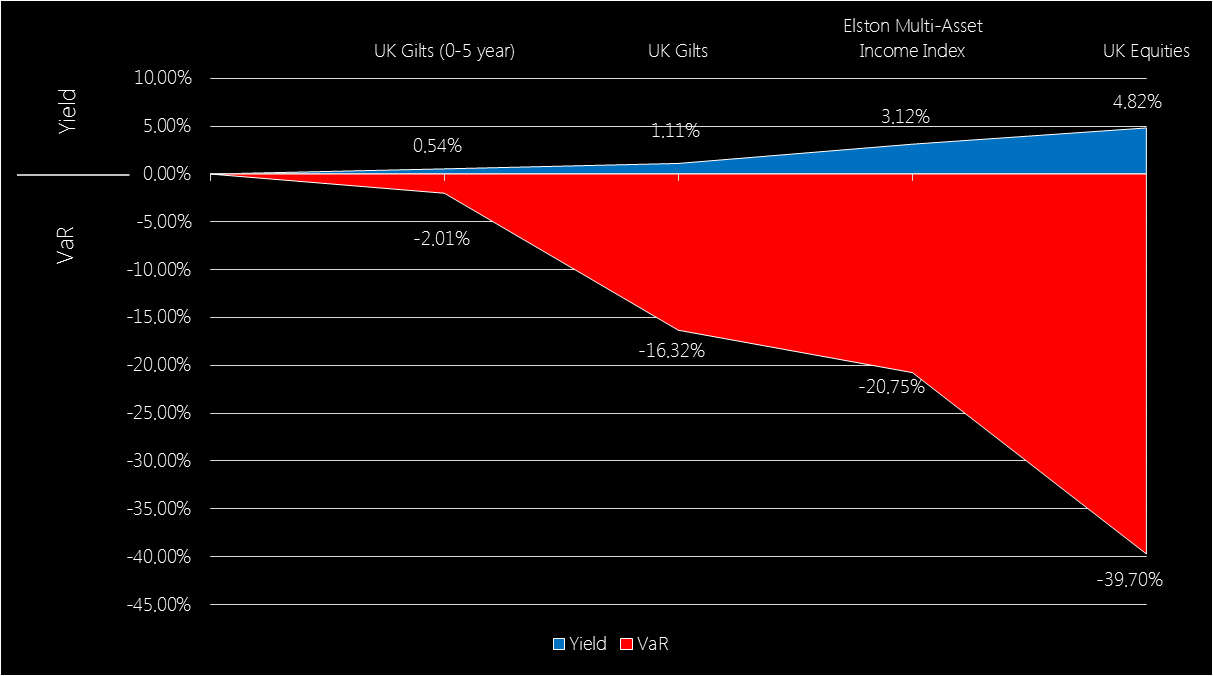

Dividend concentration risk is not new, just more visible A number of blue chip companies announced dividend reductions or suspensions in response to financial pressure wrought by the Coronavirus outbreak. This brought into light the dependency, and sometimes over-dependency, on a handful of income-paying companies for equity income investors. For UK investors in the FTSE 100, the payment of dividends from British blue chip companies provides much of its appeal. However a look under the bonnet shows a material amount of dividend concentration risk (the over-reliance on a handful of securities to deliver a dividend income). On these measures, 53% of the FTSE 100’s dividend yield comes from just 8 companies; whilst 22% of its dividend yield comes from energy companies. The top 20 dividend contributors provide 76% of the dividend yield. We measure dividend concentration risk by looking at the product of a company’s weight in the index and its dividend yield, to see its Contribution to Yield of the overall index. Fig.1. FTSE 100 Contribution to Yield, ranked Source: Elston research, Bloomberg data, as at June 2020 Quality of Income More important than the quantity of the dividend yield, is its quality. As income investors found out this year, there’s a risk to having a large allocation to a dividend payer if it cuts or cancels its dividend. Equally, there’s a risk to having a large allocation to a dividend payer, whose yield is only high as a reflection of its poor value. Screening for high dividend yield alone can lead investors into “value-traps” where the income generated looks high, but the total return (income plus capital growth) generated is low. Contrast the performance of these UK Equity Income indices, for example. Fig.2. UK Equity Income indices contrasted Source: Elston research, Bloomberg data. Total returns from end December 2006 to end June 2020 for selected UK Equity Indices. Headline Yield as per Bloomberg data as at 30th June 2020 for related ETFs. The headline yield for the FTSE UK Dividend+, FTSE 100 and S&P UK Dividend Aristocrat Indices was 8.10%, 4.44%, and 4.07% respectively as at end June 2020. However, the annualised long-run total return (income plus capital growth) 1.03%, 4.29% and 4.82% respectively. Looking at yield alone is not enough. The dependability of the dividends, and the quality of the dividend paying company are key to overall performance. Mitigating dividend concentration risk: quality yield, with low concentration The first part of the solution is to focus on high quality dividend-paying companies. One of the best indicators of dividend quality is a company’s dividend policy and track record. A dependable dividend payer is one that has paid the same or increased dividend year in, year out, whatever the weather. The second part of the solution is to consider concentration risk and make sure that companies’ weights are not skewed in an attempt to chase yield. This is evident by contrasting the different index methodologies for these equity income indices. The FTSE 100 does not explicitly consider yield (and is not designed to). The FTSE UK Dividend+ index ranks companies by their dividend yield alone. The S&P UK Dividend Aristocrats only includes companies that have consistently paid a dividend over several years, whilst ensuring there is no over-dependency on a handful of stocks. A look at the top five holdings of each index shows the results of these respective methodologies. Fig.3. Top 5 holdings of selected UK equity indices Put simply, the screening methodology adopted will materially impact the stocks selected for inclusion in an equity income index strategy. What about active managers? A study by Interactive Investor looked at the top five most commonly held stocks in UK Equity Income funds and investment trusts. For funds, the most popular holdings were GlaxoSmithKline, Imperial Brands, BP, Phoenix Group & AstraZeneca. For investment trusts, the most popular holdings are British American Tobacco, GlaxoSmithKline, RELX, AstraZeneca and Royal Dutch Sell. Unsurprisingly, each of the holdings above is also a constituent of the S&P Dividend Aristocrats index, hence ETFs that track this index simply provide a lower cost way of accessing the same type of company (dependable dividend payers with steady or increasing dividends), but using a systematic approach that enables a lower management fee. Understanding what makes dividend income dependable for an asset class such as UK equities, is only part of the picture of mitigating income risk. Income diversification is enabled by adopting a multi-asset approach. The advantage of a multi-asset approach The advantage of a multi-asset approach is two-fold. Firstly the ability to diversify equity income by geography for a more globalised approach, to benefit from economic and demographic trends outside the UK. Secondly the ability to diversify income by asset class, to moderate the level of overall portfolio risk. For investors who never need to dip into capital, have a very high capacity for loss, and can comfortably suffer the slings and arrows of the equity market, equity income works well – so long as the quality of dividends is addressed, as above. But for anyone else, where there is a need for income, but a preference for a more balanced asset allocation, a multi-asset income approach may make more sense. The rationale for a multi-asset approach is therefore to capture as much income as possible without taking as much risk as an all-equity approach. Value at Risk vs Income Reward There is always a relationship between risk and reward. For income investors, it’s no different. To be rewarded with more income, you need to take more risk with your capital. This means including equities over bonds, and, within the bonds universe, considering both credit quality (the additional yield from corporate and high yield bonds over gilts), and investment term (typically, the longer the term, the greater the yield). This overall level f risk being taken can be measured using a Value at Risk metric (a “worst case” measure of downside risk). If you want something with very low value-at-risk, shorter duration gilts can provide that capital protection, but yields are very low. Even nominally “safe” gilts, with low yields, nonetheless have potential downside risk owing to their interest rate sensitivity (“duration”). UK Equities offer a high yield, but commensurately also carry a much higher downside risk. The relationship between yield and Value-at-Risk (a measure of potential downside risk) is presented below. Fig.4. Income Yield vs Value at Risk of selected asset classes/indices Source: Elston research, Bloomberg data, as at 30th June 2020. Note: an investment with a Value at Risk (“VaR”) of -10% (1 year, 95% Confidence) means there is, to 95% confidence (a 1 in 20 chance), a risk of losing 10% of the value of your investment over any given year. Asset class data reflects representative ETFs.

Our Multi-Asset Income index has, unsurprisingly, a risk level between that of gilts and equities, and captures approximately 65% of the yield, but with only 52% of the Value-at-Risk. Summary How you get your income – whether from equities, bonds or a mix – is critical to the amount of risk an investor is willing and able to take, and is a function of asset allocation. Understanding the asset allocation of an income funds is key to understanding its risks (for example, Volatility, Value at Risk and Max Drawdown). The dependability of dividend income you receive - whether from value traps or quality companies; whether concentrated or diversified – is a function of security selection. This can be either manager-based (subjective), or index-based (objective). For investors requiring a dependable yield, a closer look at how income is generated – through asset allocation and dividend dependability – is key. |

ELSTON RESEARCHinsights inform solutions Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Company |

Solutions |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed