|

[5 min read, open as pdf]

For someone aged 65 with average life expectancy a bond fund isn’t enough to ensure portfolio durability. Over that term the biggest risk is inflation risk and it’s harder for nominal bonds to keep pace with inflation. Inflation-linked bonds bring in high interest rate sensitivity (duration). Whilst higher yields now make for a more interesting entry point, there’s plenty of solid yield available in high quality low cost index bond funds.

But to navigate the changing outlook within the bond market a managed bond fund should also be considered as a one stop diversified managed bond portfolio. Most retirees will need a multi-asset retirement portfolio to last the course. Bonds alone are not enough. Read the quote in Trustnet Momentum does not care about sectors, themes, or valuations. In this article for ETF Stream, Hoshang Daroga explores the Momentum factor.

Whilst the original Fama & French research isolated 3 factors (Market risk (Beta), Size and Value) that were found to be persistent drivers of returns, research has since evolved to look at other factors such as Quality, Yield, Momentum and Minimum Volatility. Read in full Our head of fund research, Jackie Qiao, shares her desert island fund picks with Citywire.

Read in full [5 min read, as pdf]

The purpose of including alternatives in a portfolio, is for one reason: diversification. But how can we be sure alternatives are doing their job?

Read the full article in FT Adviser or watch the CISI-endorsed CPD webinar Whether using bond funds or investing directly, bond investing requires thinking about the outlook for interest rates, inflation expectation, credit spreads and currency direction (if applicable) and how those variables impact bond valuations.

Read the article in FT Adviser For investors wanting a differentiated approach to implementing a global equity exposure, what are the options?

Read the full article in FT Adviser [5min read, open as pdf]

[5min read, open as pdf]

[3 min read, open as pdf]

Watch the CISI-endorsed CPD webinar on this topic [5 min, open as pdf]

[3 min read, open as pdf ]

[5 min read, open as pdf]

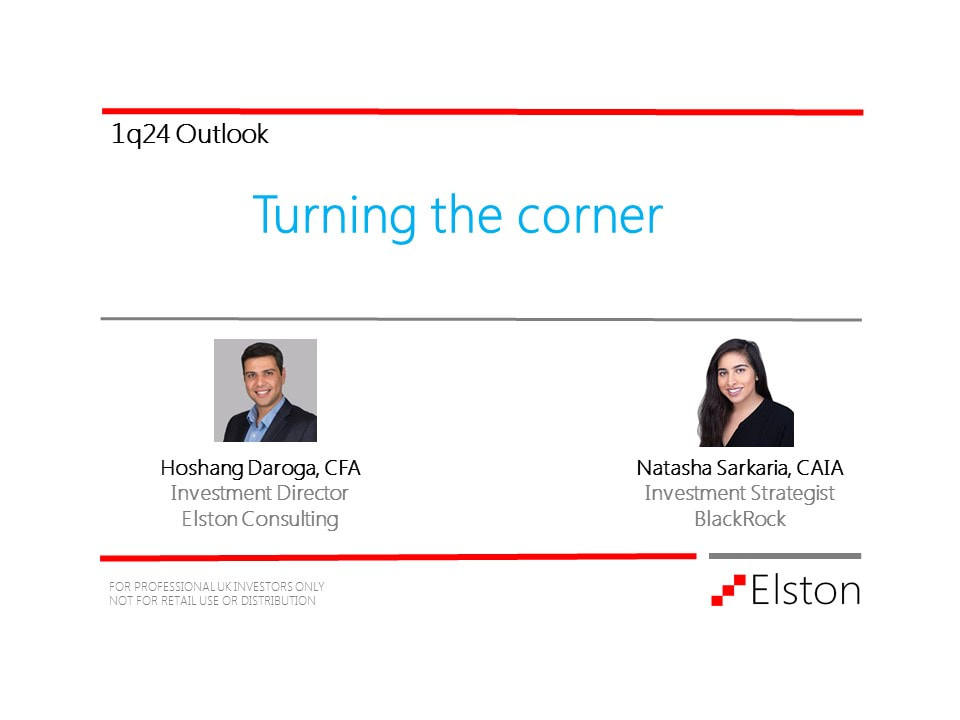

In our upcoming quarterly investment outlook, we update our key themes for 2024. Please join Hoshang Daroga (Elston Consulting) and Natasha Sarkaria (BlackRock) for this webinar.

Our key themes are: 1. Growth: Steady as she slows 2. Rates: Perfecting the pivot 3. Inflation: Ensuring portfolio resilience Our full Quarterly Investment Outlook is available to our clients. Watch the Webinar Central Banks' policy rates are expected to pivot towards cuts in 2024 with a material impact on asset class perspectives.

Read the full article in FT Adviser |

ELSTON RESEARCHinsights inform solutions Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Company |

Solutions |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed