|

Investors should prefer the certainty of index funds which track the index less passive fees, than the hope and disappointment of active funds which, in aggregate, track the index less active fees.

In this series of articles, I look at some of the key topics explored in my book “How to Invest With Exchange Traded Funds” that also underpin the portfolio design work Elston does for discretionary managers and financial advisers. Clarifying terms We believe that typically an index fund or ETF can perfectly well replace an active fund for a given asset class exposure. As with all disruptive technologies, many column inches have been dedicated to the “active vs passive” debate. However, with poorly defined terms, much of this is off-point. If active investing is referring to active (we prefer “dynamic”) asset allocation: we fully concur. There need be no debate on this topic. Making informed choices on asset allocation – either using a systematic or non-systematic decision-making process – is an essential part of portfolio management. If, however, active investing refers to fund manager or security selection, this is more contentious, and this should be the primary topic of debate. Theoretical context: the Efficient Market Hypothesis The theoretical context for this active vs passive debates is centred on the notion of market efficiency. The efficient market hypothesis is the theory that all asset prices reflect all the available past and present information that might impact that price. This means that the consistent generation of excess returns at a security level is impossible. Put differently, it implies that securities always trade at their fair value making it impossible to consistently outperform the overall market based on security selection. This is consistent with the financial theory that asset prices move randomly and thus cannot be predicted . Putting the theory into practice means that where markets are informationally efficient (for example developed markets like the US and UK equity markets), consistent outperformance is not achievable, and hence a passive investment strategy make sense (buying and holding a portfolio of all the securities in a benchmark for that asset class exposure). Where markets are informationally inefficient (for example frontier markets such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Vietnam ) there is opportunity for an active investment strategy to outperform a passive investment strategy net of fees. Our view is that liquid indexable markets are efficient and therefore in most cases it makes sense to access these markets using index-tracking funds and ETFs, in order to obtain the aggregate return for each market, less passive fees. This is because, owing to the poor arithmetic of active management, the aggregate return for all active managers is the index less active fees. The poor arithmetic of active management Bill Sharpe, the Nobel prize winner, and creator of the eponymous Sharpe Ratio, authored a paper “The Arithmetic of Active Management” that is mindblowing in its simplicity, and is well worth a read. We all know the criticism of passive investing by active managers is that index fund [for a given asset class] delivers the performance of the index less passive fees so is “guaranteed” to underperform. That’s true, but it misses a major point. The premise of Sharpe’s paper is that the performance, in aggregate, of all active managers [for a given asset class] is the index less active fees. Wait. Read that again. Yes, that’s right. The performance of all active managers is, in aggregate (for a given asset class) the index less active fees. Sounds like a worse deal than an index fund? It’s because it is. How is this? Exploring the arithmetic of active Take the UK equity market as an example. There are approximately 600 companies in the FTSE All Share Index. Now imagine there are only two managers of two active UK equity funds, Dr. Star and Dr. Dog. Dr. Star consistently buys, with perfect foresight, the top 300 performing shares of the FTSE All Share Index each year, year in year out, consistently over time. This is because he avoids the bottom 300 worst performing shares. His performance is stellar. That means there are 300 shares that Dr. Star does not own, or has sold to another investor, namely to Dr. Dog. Dr. Dog therefore consistently buys, with perfect error, the worst 300 performing shares of the FTSE All Share Index each year, year in year out, consistently over time. His performance is terrible. However, in aggregate, the combined performance of Dr. Star and Dr. Dog is the same as the performance of the index of all 600 stocks, less Dr. Star’s justifiable fees, and Dr. Dog’s unjustifiable fees. The performance of both active managers is, in aggregate, the index less active fees. It’s a zero sum game. In the real world the challenge of persistency – persistently outperforming the index to be Dr.Star – means that over time it is very hard, in efficient markets to persistently outperform the index. So investors have a choice. They can either pay a game of hope and fear, hoping to consistently find Dr. Star as their manager. Or they can be less exciting, rational investor who focus on asset allocation and implement it using index fund to buy the whole market for a given asset exposure keep fees down. Given this poor “arithmetic” of active management, why would you ever chose an active fund (in aggregate, the index less active fees) over a passive fund (in aggregate the index less passive fees)? Quite. Monitoring performance consistency The inability of non-index active funds to consistently outperform their respective index is evidenced both in efficient market theory, and in practice. Consistent with the Efficient Market Hypothesis, studies have shown that actively managed funds generally underperform their respective indices over the long-run and one of the main determinant of performance persistency is fund expenses . Put differently, lower fee funds offer better value for money than higher fee funds for the same given exposure. This is a key focus area from the UK regulator as outlined in the Asset Management Market Study. In practice, the majority of GBP-denominated funds available to UK investors have underperformed a related index over longer time horizons. Whilst the percentage of funds that have beaten an index over any single year may fluctuate from year to year, no active fund category evaluated has a majority of outperforming active funds when measured over a 10-year period. This tendency is consistent with findings on US and European based funds, based on the regularly published “SPIVA Study”. The poor value of active managers who “closet index” “Closet indexing” is a term first formalised by academics Cremers and Petajisto in 2009 . It refers to funds whose objectives and fees are characteristic of an active fund, but whose holdings and performance is characteristic of a passive fund. Their study and metrics around “active share” and “closet indexing” caused a stir in the financial pages on both sides of the Atlantic as active fund managers started to watch the persistent rise of ETFs and other index-tracking products. The issue around closet index funds is not simply about fees. It’s as much about transparency and customer expectations. Understanding Active Share Active Share is a useful indicator developed by Cremers and Petajisto as to what extent an active (non-index) fund is indeed “active”. This is because whilst standard metrics such as Tracking Error look at the variability of performance difference, active share looks at to what extent the weight of the holdings within a fund are different to the weight of the holdings within the corresponding index. The higher the Active Share, the more likely the fund is “True Active”. The lower the Active Share, the more likely the fund is a “Closet Index”. How can you define “closet indexing”? There has been some speculation as to what methodology the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) used to deem funds a “closet index”. In this respect, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), the pan-European regulator’s 2016 paper may be informative. Their study applied a screen to focus on funds with 1) assets under management of over €50m, 2) an inception date prior to January 2005, 3) Fees of 0.65% or more, and 4) were not marketed as index funds. Having created this screen, ESMA ran three metrics to test for a fund’s proximity to an index: active share, tracking error and R-Squared. On this basis, a fund with low active share, low tracking error and high R-Squared means it is very similar to index-tracking fund. Based on ESMA’s criteria, we estimate that between €400bn and €1,200bn of funds available across the EU could be defined as “closet index” funds. That’s a lot of wasted fees. Defining “true active” We believe there is an essential role to play for “true active”. By this we mean high conviction fund strategies either at an asset allocation level. True active (asset allocation level): at an asset allocation level, hedge funds which have the ability to invest across assets and have the ability to vary within wide ranges their risk exposure (by going both long and short and/or deploying leverage) would be defined as “true active”. Target Absolute Return (TAR) funds could also be defined as true active given the nature of their investment process. Analysing their performance or setting criteria for performance evaluation is outside the scope of this book. However given the lacklustre performance both of Hedge Funds in aggregate (as represented by the HFRX index) and of Target Absolute Return funds (as represented by the IA sector performance relative to a simple 60/40 investment strategy), emphasises the need for focus on manager selection, performance consistency and value for money. True active (fund level): we would define true active fund managers as those which manage long-only investments, either in hard-to-access asset classes or those which manage investments in readily accessible asset classes but in a successfully idiosyncratic way. It is the last group of “active managers” that face the most scrutiny as their investment opportunity set is identical to that of the index funds that they aim to beat. True active managers in traditional long-only asset classes must necessarily take an idiosyncratic non-index based approach. In order to do so, they need to adopt one or more of the following characteristics, in our view:

Their success, or otherwise, will depend on the quality of their skill and judgement, the quality of their internal research resource, and their ability to absorb and process information to exploit any information inefficiencies in the market. True active managers who can consistently deliver on objectives after fees will have no difficulty explaining their skill and no difficulty in attracting clients. By blending an ETF portfolio with a selection of true active funds, investors can reduce fees on standard asset class exposures to free up fee budget for genuinely differentiated managers. Summary In conclusion, “active” and “passive” are lazy terms. There is no such thing as passive. There is static and dynamic asset allocation, there is systematic and non-systematic tactical allocation, there is index-investing and non-index investing, there are traditional index weighting and alternative index weighting schemes. The use of any or all of these disciplines requires active choices by investors or managers. [2 minute read, open as pdf] Sign up for our upcoming webinar on incorporating ESG into model portfolios Summary

Defining terms With a growing range of ethical investment propositions available to portfolio designers, we first of all need to define and disambiguate some terms.

Criteria-based approach works well for indices Applying ESG criteria to a universe of equities acts as a filter to ensure that only investors are only exposed to companies that are compatible with an ESG investment approach. Creating a criteria-based approach requires a combination of screening, scoring and weighting. Looking at the MSCI World SRI 5% Capped Index, for example, means:

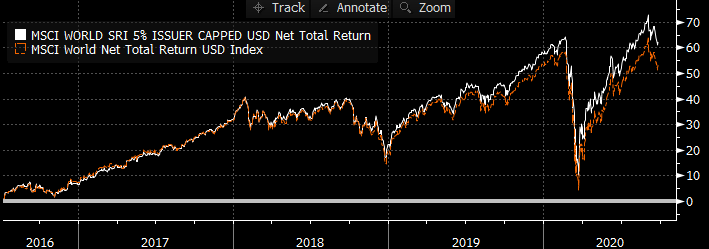

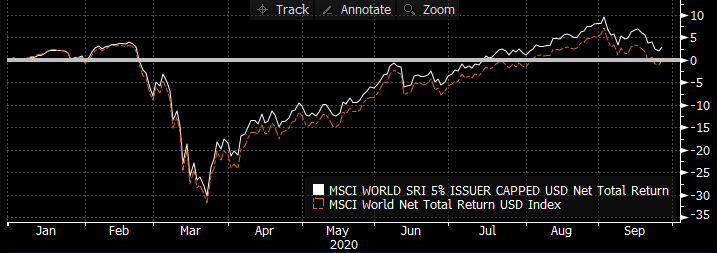

Indices codify criteria An index is “just” a weighting scheme based on a set of criteria. A common, simple index is to include, for example, the 100 largest companies for a particular stock market. SRI indices reflect weighting schemes, albeit more complex, but importantly, represent a systematic (rules-based) and hence objective approach. However, the appropriateness of those indices is as only as good as their methodology and the quality of the screening, scoring and weighting criteria applied. Proof of the pudding To mix metaphors, the proof of the pudding is in the making of performance that is consistent with the parent index, whilst reflecting all the relevant scoring and screening criteria. This allows investors to have their ESG cake, as well as eating its risk-return characteristics. Contrast, for example, the MSCI World Index with the MSCI World Socially Responsible Investment 5% Issuer Capped Index. The application of the screening and scoring reduces the number of companies included in the index from 1,601 to 386. But the weightings adjustments are such that the relative risk-return characteristics are similar: the SRI version of the parent index has a Beta of 0.98 to the parent index and is 99.4% correlated with the parent index. Fig.1. Comparative long-term performance Source: Bloomberg data Fig.2. Year to Date Performance Source: Bloomberg data,

Focus on compliance, not hope of outperformance Indeed pressure on the oil price and the performance of technology this year (technology firms typically have strong ESG policies) means that SRI indices have slightly outperformed parent indices. However, our view is that ESG investing should not be backing a belief that performance should or will be better than a mainstream index. In our view, ESG investing should aim to deliver similar risk-return characteristics to the mainstream index for a given exposure but with the peace of mind that the appropriate screening and scoring has been systematically and regularly applied. [1] For more on this ratings methodology, see https://www.msci.com/esg-ratings What kind of investor are you: a stock selector, a manager selector or an index investor?

In this series of articles, I look at some of the key topics explored in my book “How to Invest With Exchange Traded Funds” that also underpin the portfolio design work Elston does for discretionary managers and financial advisers. In previous articles, we looked at things to consider when designing a multi-asset portfolio. Let’s say, for illustration, an investor decides on a balanced portfolio invested 60% in equities and 40% in bonds. The “classic” 60/40 portfolio. You now have a number of options of how to populate the equity allocation within that portfolio. We look at each option in turn. Equity exposure using direct equities: “the stock selectors” This is the original approach, and, for some, the best. We call this group “Stock Selectors”: investors who prefer to research and select individual equities and construct, monitor and manage their own portfolios. To achieve diversification across a number of equities, a minimum of 30 stocks is typically required (at one event I went to for retail investors I was slightly nervous when it transpired that most people attending held fewer than 10 stocks in their portfolio). Across these 30 or more stocks, investors should give due regards to country and sector allocations. Some golden rules of stock picking would include:

The advantage of investing in direct equities is the ability to design and manage your own style, process and trading rules. Also by investing direct equities there are no management fees creating performance drag. But when buying and selling shares, there are of course transactional, and other frictional costs, such as share dealing costs and Stamp Duty. The most alluring advantage of this approach is the potential for index-beating and manager-beating returns. But whilst the potential is of course there, as with active managers, persistency is the problem. The more developed markets are “efficient” which means that news and information about a company is generally already priced in. So to identify an inefficiency you need an information advantage or an analytical advantage to spot something that most other investors haven’t. Ultimately you are participant in a zero-sum game, but the advantage is that if you can put the time, hours and energy in, it’s an insightful and fascinating journey. The disadvantage of direct equity is that if it requires at least 30 stocks to have a diversified portfolio, then it requires time, effort and confidence to select and then manage those positions. The other disadvantage is the lack of diversification compared to a fund-based approach (whether active or passive). This means that direct investors are taking “stock specific risks” (risks that are specific to a single company’s shares), rather than broader market risk. In normal markets, that can seem ok, but when you have occasional outsize moves owing to company-specific factors, you have to be ready to take the pain and make the decision to stick with it or to cut and run. What does the evidence say? The evidence suggests that, in aggregate, retail investors do a poor job at beating the market. The Dalbar study in the US, published since 1994, compares the performance of investors who select their own stocks relative to a straightforward “buy-and-hold” investment in an index funds or ETF that tracks the S&P500, the benchmark that consists of the 500 largest traded US companies. The results consistently show that, in aggregate, retail investors fare a lot worse than an index investor. Reasons for this could be for a number of reasons, including, but not limited to:

But selecting the “right” 30 or more stocks is labour-intensive, and time-consuming. So if you enjoy this and are confident doing this yourself, then there’s nothing stopping you. Indeed, you may be one of the few who can, or think you can, consistently outperform the index year in, year out. But it’s worth remembering that the majority of investors don’t manage to. For most people, a direct equity/direct bond portfolio is overly complex to create, labour intensive to manage and insufficiently diversified to be able to sleep well at night. Furthermore owning bonds directly is near impossible owing to the high lot sizes. So why bother? Investors who want to leave stock picking to someone else have two options to be “fund” investors selecting active funds. Or “index” investors selecting passive funds. Equity exposure using active funds: the “manager selectors” A fund based approach means holding a single investment in fund which in turn holds a large number of underlying equities, or bonds, or both. Investor who want to leave it to an expert to actively pick winners and avoid losers can pick an actively managed fund. We call this group “Manager Selectors”. But then you have to pick the “right” actively managed fund, which also takes time and effort to research and select a number of equity funds from active managers, or seek out “star” managers who aim to consistently outperform a designated benchmark for their respective asset class. And whilst we all get reminded that past performance is not an indicator of future performance, there isn’t much else to go by. In this respect access to impartial independent research and high quality,unbiased fund lists is an invaluable time-saving resource. The advantage of this approach that with a single fund you can access a broadly diversified selection of stocks picked by a professional. The disadvantage of this approach is that management fees are a drag on returns and yet few funds persistently outperform their respective benchmark over the long-run raising the question as to whether they are worth their fees. This is evidenced in a quarterly updated study known as the SPIVA Study, published by S&P Dow Jones Indices, which compares the persistency of active fund performance relative to asset class benchmarks. For efficient markets, such as US & UK equities, the results are usually quite sobering reading for those who are prefer active funds. Indeed many so-called active funds have been outed as “closet index-tracking funds” charging active-style fees, for passive-like returns. So of course there are “star” managers who are in vogue for a while or even for some time. But it’s more important to make sure a portfolio is properly allocated, and diversified across managers, as investors exposed to Woodford found out. In my view, an all active fund portfolio is overly expensive for what it provides. Whilst the debate around stock picking will run and run (and won’t be won or lost in this article), consider at least the bond exposures within a portfolio. An “active” UK Government Bond fund has the same or similar holdings to a “passive” index-tracking UK Government Bond fund but charges 0.60% instead of 0.20%, with near identical performance (except greater fee drag). Have you read about a star all-gilts manager in the press? Nor have I. So why pay the additional fee? What about hedge funds? Hedge funds come under the “true active” category because overall allocation exposure can vary greatly, and there is the ability to position a fund to benefit from falls or rises in securities or whole markets, and the ability to borrow money to invest more than the fund’s original value. But most “true active” hedge funds are not available to retail investors who are more limited to traditional “long-only” retail funds for each asset class. Equity exposure using index funds: the “index investor” Investors who don’ want the time, hassle or cost of picking active managers, or believe that markets are “efficient” often use passive index-tracking funds. We call this group “Index Investors” (full disclosure: I am a member of this group!). These are investors who want to focus primarily on getting the right asset allocation to achieve their objectives, and implement and actively manage that asset allocation but using low cost index funds and/or index-tracking ETFs. The advantage of this approach is transparency around the asset mix, broad diversification and lower cost relative to active managers. The disadvantage of this approach is that it sounds, well, boring. Ignoring the news on companies’ share prices are up or down and which single-asset funds are stars and which are dogs would mean 80% of personal finance news and commentary becomes irrelevant! On this basis, my preference is to be a 100% index investor – the asset allocation strategy may differ for the different objectives between my parents, myself and my kids. But the building blocks that make up the equity, bond and even alternative exposures within those strategies can all index-based. A blended approach Whilst my preference is to be an index investor, I don’t disagree, however, that it’s interesting, enjoyable and potentially rewarding for some retail investors and/or their advisers to spend time choosing managers and picking stocks, where they have high conviction and/or superior insight. Traditionally the bulk of retail investors were in active funds. This is extreme. More and more are becoming 100% index investors: this is also extreme. There’s plenty of ground for a common sense blended approach in the middle. For cost, diversification and liquidity reasons, I would want the core of any portfolio to be in index funds or ETFs. I would want the bulk of my equity exposure to be in index funds, with moderate active fund exposure to selected less efficient markets (for example) small caps, and up to 10% in a handful of direct equity holdings that you follow, know and like. What would a blended approach look like for a 60/40 equity/bond portfolio? 60% equity of which Min 70% index funds/ETFs Max 20% active funds Max 10% direct equity “picks”/ideas 40% bonds of which 100% index funds Summary For most investors, investing is something that needs to get done, like opening a bank account. If you are in this group then using a ready-made model portfolio or low-cost multi-asset fund, like a Target Date Fund, may make sense. For some investors, investing is more like a hobby – something that you are happy to spend time and effort doing. If you are in this group, you have to decide if you are a Stock Selector, Manager Selector or Index Investor, or a blend of all three, and research and build your portfolio accordingly.

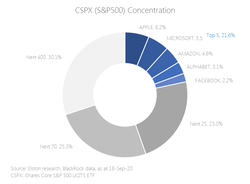

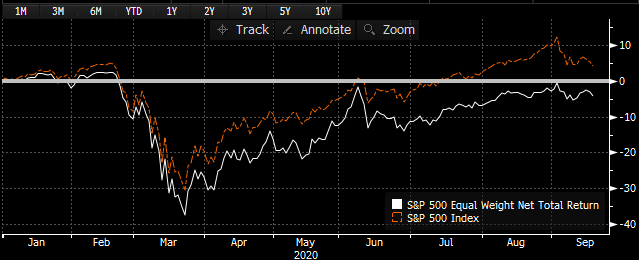

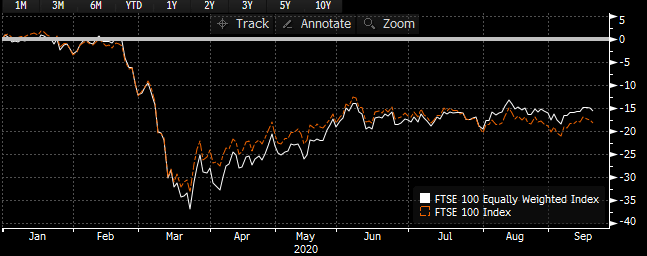

Focus on index methodology Methodology is the genetic code of an index. The rules that govern how an index is constructed determines what’s in it, at what weights, and therefore how it will perform in relation to the performance of all its components. A handful of (mainly older) indices are price-weighted indices (such as the DJIA (in the US, since 1896), FT30 (in the UK, since 1935), and Nikkei 225 (in Japan, since 1950). This means the weight of each stock in the index is determined by its price relative to the summed prices of all the constituents of the index. The bulk of the most familiar, and most tracked, indices are capitalisation-weighted indices. This means the weight of each stock in the index is determined by its (often free-float-adjusted) market capitalisation relative to the aggregated market capitalisation of all the constituents of the index. This leads to one of an oft-cited critique of mainstream indices that they become “pro-cyclical”: namely, they allocate an increasing weight to the best performing stocks, and a decreasing weight to the worst performing stocks. This is true, but is coloured by your view as to which comes first, the stock performance chicken, or the index performance egg. Looking at concentration risk What is certainly true is that changes in company capitalisation can create significant stock concentrations in mainstream indices. For example, the top 5 holdings in the S&P 500 (Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet and Facebook) currently represent 21.6% of that index. The top 30 stocks represent 44.6%, and the top 100 stocks represent 69.9%. The remaining 400 stocks are a long tail of relatively smaller companies whose individual change in value will not materially impact the overall index performance. Fig.1. S&P500 Concentration  Size-bias is a choice not an obligation Index concentration, and related “size-bias”, the relative over-weighting of the largest companies, is however a choice, not an obligation for index investors. The existence of equal-weight indices enable a less concentrated exposure to the same components of an index. Whilst this solves the stock concentration risk, it creates a “Fear of Missing Out risk” when those large stocks are doing well. So, if choosing to use an equal-weighted index to reduce dependency on a concentrated index, communication is key. Reducing stock-specific risk may be welcome with end clients in theory, but clear messaging is required to explain that investment performance will not be comparable to the performance of funds (whether active or passive) using traditional capitalisation weighted benchmarks. End investors may feel they miss out when sentiment in the largest names is strong. But will be relieved when the reverse applies. On the basis that many investors are asymmetrically loss-averse, the more evenly distributed stock risk of an equal-weighted index could be something to consider. But only once any potential “Fear of Missing Out” has been discussed and addressed. Fig.2. S&P 500 vs S&P 500 Equal Weight, YTD Performance (USD terms); Fig.3. & FTSE 100 vs FTSE 100 Equal Weight, YTD Performance (GBP terms) Source: Elston Research, Bloomberg data, as at 18-Sep-20

Index selection is an active choice There’s no such thing as passive. Index investing is about adopting a systematic, rules-based approach to stock selection. There is an active choice to be made around methodology and index selection. If you don’t want to always hold the largest stocks, then don’t use a cap-weighted index. If you want to hold stocks based on other criteria – their earnings, their dividends, their style, or just equally weighted – there are plenty of other indices to choose from. It’s up to the index investor to make that active choice. While there are no shortage of limitations and no “right” answers, portfolio theory nonetheless remains, rightly, the bedrock of traditional multi-asset portfolio design.

In this series of articles, I look at some of the key topics explored in my book “How to Invest With Exchange Traded Funds” that also underpin the portfolio design work Elston does for discretionary managers and financial advisers. Portfolio theory in a nutshell Portfolio theory, in a nutshell, is a framework as to how to construct an “optimised” portfolio using a range of asset classes, such as Equities, Bonds, Alternatives (neither equities nor bonds) and Cash. An “optimised” portfolio has the highest unit of potential return per unit of risk (volatility) taken. The aim of a multi-asset portfolio is to maximise expected portfolio returns for a given level of portfolio risk, on the basis that risk and reward are the flipside of the same coin. The introduction of “Alternative” assets, that are not correlated with equities or bonds (so that one “zigs” when the other “zags”), helps diversify portfolios, like a stabilizer. Done properly, this can help reduce portfolio volatility to less than the sum of its parts. Whilst the framework of Modern Portfolio Theory was coined by Nobel laureate Harry Markowitz in 1952, the key assumptions for portfolios theory – namely which asset classes, their returns, risk and correlations are, by their nature, just estimates. So using portfolio theory as a guide to designing portfolios is only as good as the quality of the inputs assumptions selected by the user. And those assumptions are ever-changing. Furthermore, the constraints imposed when designing or optimising a portfolio will determine the end shape of the portfolio for any given optimisation. And those constraints are subjective to the designer. So portfolio design is part art, part science, and part common sense. Whilst there are no shortage of limitations and no “right” answers, portfolio theory nonetheless remains, rightly, the bedrock of traditional multi-asset portfolio design. What differentiates multi-asset portfolios? A portfolio’s asset allocation is the key determinant of portfolio outcomes and the main driver of portfolio risk and return. Ensuring the asset allocation is aligned to an appropriate risk-return objective is therefore essential. Getting and keeping the asset allocation on track for the given objectives and constraints is how portfolio managers – whether of model portfolios or of multi-asset funds – can add most value for their clients. There are no “secrets” to asset allocation in portfolio management. It is perhaps one of the most well-studied and researched fields of finance. Stripping all the theory down to its bare bones, there are, in my view, three key decisions when designing multi-asset portfolios:

Strategic allocation is expected to answer the key questions of what are a portfolio’s objectives, and what are its constraints. The mix of assets is defined such as to maximise the probability of achieving those objectives, subject to any specified constraints. Objectives can be, for example:

Strategic allocations should be reviewed possibly each year and certainly not less than every 5 years. This is because assumptions change over time, all the time. Static vs Dynamic One of the key considerations when it comes to managing an allocation is to whether to adopt a static or dynamic approach. A strategy with a “static” allocation, means the portfolios is rebalanced periodically back to the original strategic weights. The frequency of rebalancing can depend on the degree of “drift” that is allowed, but constrained by the frictional costs involved in implementing the rebalancing. A strategy with a “dynamic” approach, means the asset allocation of the portfolios changes over time, and adapts to changing market or economic conditions. Dynamic or Tactical allocation, can be either with return-enhancing objective or a risk-reducing objective or both, or optimised to some other portfolio risk or return objective such as income yield. For very long-term investors, such as endowment funds, a broadly static allocation approach will do just fine. Where very long-term time horizons are involved, the cost of trading may not be worthwhile. As time horizons shorten, the importance of a dynamic approach becomes increasingly important. Put simply, if you were investing for 50 years, tactical tweaks around the strategic allocation, won’t make as big a difference as if you were investing for just 5 years. This is because risk (as defined by volatility) is different for different time frames, and is higher for shorter time periods, and lower for longer time periods. In a way this is also just common sense. If you are saving up funds to buy a house, you will invest those funds differently if you are planning to buy a house in 3 years or 30 years. Time matters so much as it impacts objectives and constraints, as well as risk and return. Access Preferences Managers need to make implementation decisions as regards how they access particular asset classes or exposures – with direct securities, higher cost active/non-index funds, or lower cost passive/index funds and ETFs. Fund level due diligence as regards underlying holdings, concentrations, round-trip dealing costs and internal and external fund liquidity profiles are key in this respect. The choice between direct equities, higher cost active funds or lower cost index funds is a key one and is the subject of a later article. Types of multi-asset strategy There is a broad range of multi-asset strategies available to investors, whose relevance depends on the investor’s needs and preferences. To self-directed investors, these multi-asset portfolios are made easier to access and monitor through multi-asset funds, many of which are themselves constructed wholly or partly with index funds and/or ETFs. We categorise multi-asset funds into the following groups (using our own naming conventions based on design: these do not exist as official “multi-asset sectors”, unfortunately): Relative Risk Relative risk strategies target a percentage allocation to equities so the risk and return of the strategy is in consistent relative proportion the (ever-changing) risk and return of the equity markets. This is the most common approach to multi-asset strategies. Put differently, asset weights drive portfolio risk. Examples include Vanguard LifeStrategy, HSBC Global Strategy and other traditional multi-asset funds. Target Risk Target risk strategies target a specific volatility level or range. This means the percentage allocation to equities is constantly changing to preserve a target volatility band. Put differently, portfolio risk objectives drive asset weights. Examples of this approach include BlackRock MyMap funds. Target Return Target return strategies target a specific return level in excess of a benchmark rate e.g. LIBOR, and take the required risk to get there. This is good in theory for return targeting, but results are not guaranteed. Examples of this approach include funds in the Target Absolute Return sector, such as ASI Global Absolute Return. Target Date Target Date Funds adapt an asset allocation over time from higher risk to lower, expecting regular withdrawals after the target date. This type of strategy works as “ready-made” age-based fund whose risk profile changes over time. Examples of target date funds include Vanguard Target Retirement Funds, and the Architas BirthStar Target Date Funds (managed by AllianceBernstein)*. Target Income Target income funds target an absolute level of income or a target distribution yield. Examples of this type of fund include JPMorgan Multi-Asset Income. Target Term Funds These exist in the US, but not the UK, and are a type of fund that work like a bond: you invest a capital amount at the beginning, receive a regular distribution, and then receive a capital payment at the end of the target term. For self-directed investors, choosing the approach that aligns best to your needs and requirements, and then selecting a fund within that sub-sector that has potential to deliver on those objectives – at good value for money – is the key decision for building a robust investment strategy. The (lack of) secrets The secret is, there are no secrets. Good portfolio design is about informed common senses. It means focusing on what will deliver on portfolio objectives and making sure those objectives are clearly identifiable by investors. Designing and building your own multi-asset portfolio is interesting and rewarding. Equally there are a range of ready-made options to chose from. The most important question is to consider to what extent a strategy is consistent with your own needs and requirements. * Note: funds referenced do not represent an endorsement or personal recommendation. Disclosure: until 2015, Elston was involved in the design and development of this fund range, but now receives no commercial benefit from these funds.

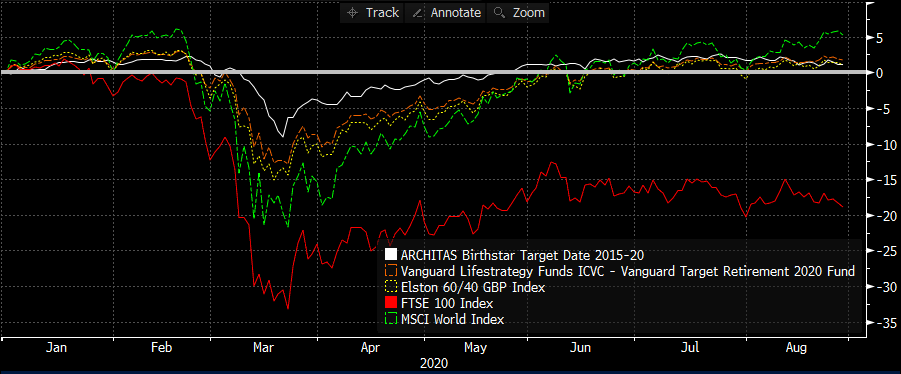

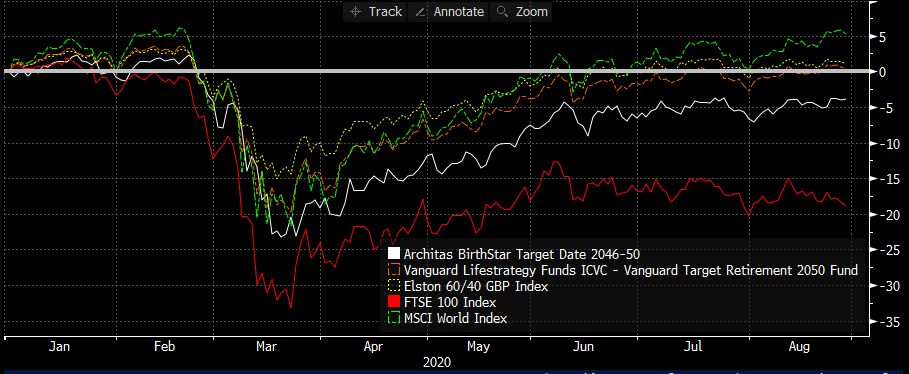

Target Date Funds are multi-asset funds whose risk profile changes over time, becoming less risky on approach to, and after the target date in the fund’s name. Investors, or their advisers, can use target date funds as an investment strategy that is purpose-built for retirement. By selecting a fund whose target date matches a planned retirement year, investors get access to an accumulation-oriented investment strategy prior to the target date, and a decumulation-oriented strategy after the target date. This makes target date funds a convenient “all-in one” fund which explains why they are often used as default funds within pension schemes, including NEST. Why a cohort-based approach makes sense It’s common sense that the risk capacity for an investor’s exposure to market risk is different at different stages of life and wealth levels. For younger investors, where wealth levels are typically lower and time horizons are longer, there is a higher capacity for loss, hence a higher exposure to higher risk-return assets makes sense. For older investors, where wealth levels are typically higher and time horizons are shorter, there is a lower capacity for loss, hence a lower exposure to higher risk-return assets makes sense. If customers can be segmented by cohorts, it makes sense that investment strategy can be too. What is the performance experience for different cohorts this year (time-weighted)? The 2015-20 Target Date Fund from Architas experienced a moderate maximum monthly drawdown of -4.71% in March 2020. By comparison, the 2020 Target Date Fund from Vanguard experienced a -6.66% drawdown. This contrasts with -9.37% for the Elston 60/40 GBP Index, -10.94% for MSCI World, and -13.81% for the FTSE 100, all in GBP terms. In this respect, investors who were in default decumulation strategies, with lower capacity for loss, saw better mitigation of downside risk relative to a traditional 60/40 “balanced” mandate. Fig.1. YTD performance of UK Target Date Funds (GBP terms) for those retiring 2015-20. Source: Elston research, Bloomberg data For investors in accumulation with target retirement date in the future, a comparison of the 2050 Target Date Funds shows Vanguard outperforming Architas – presumably owing to a more aggressive equity allocation in its glidepath. Both ranges of TDFs clearly have a low domestic equity bias, given their outperformance of the FTSE 100. Fig.2. YTD performance of UK Target Date Funds (GBP terms) for those retiring 2046-50 Source: Elston research, Bloomberg data

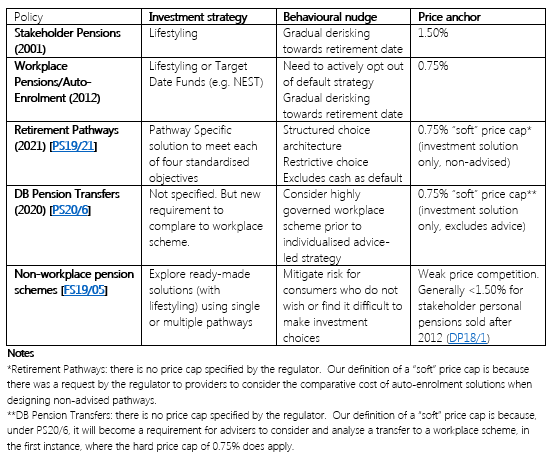

How Target Date Funds could fit in with policy evolution Ensuring there is some form of in-built lifestyling is a longstanding feature of consumer protections for pensions investment since Stakeholder times. Using behavioural finance in proposition design can provide a degree of consumer protection from poor outcomes for less confident, less engaged investors. That’s why a growing number of regulatory interventions incorporate some form of built-in lifestyling. Whilst this is complex to achieve from an administrative perspective, the fact that Target Date Funds deliver lifestyling within the multi-asset fund structure makes them a useful product type for default investment strategies. Fig.3. Key behavioural aspects and price anchors of policy interventions In this series of articles, I look at some of the key topics explored in my book “How to Invest With Exchange Traded Funds” that also underpin the portfolio design work Elston does for discretionary managers and financial advisers.

Aligning investment strategy with objectives Investing can be defined as putting capital at risk of gain or loss to earn a return in excess of what can be received from a risk-free asset such as cash or a government bond over the medium-to long-term. There can be any number of motives for investing: it could be to fund a future retirement via a SIPP, or to fund future university fees via a JISA. Online tools and calculators can help estimate how much is required to invest today to fund goals in the future. Investors can target a particular return, but learn to understand that the higher the required return, the higher the required level of portfolio risk. Risk and return are the “ying and yang” of investment. You can’t get one without the other. Total return can be broken down into income yield (dividends from equities and interest from bonds) and capital growth. In the UK, income and gains are taxed at different rates. If investing within a tax-efficient account, like a SIPP or an ISA, then income and gains are tax-free. If investing outside a tax-efficient account, investors must also then consider in their objectives how they want to receive total return – with a bias towards income or with a bias towards growth. Given the majority of DIY investors are able to make use of tax-efficient accounts, there is less need to consider income or growth, with many investors opting to focus on Total Returns and to use funds that offer “Accumulating” units that reinvest income, and reflect a fund’s total return. How then to build a portfolio to deliver an appropriate level of risk-return? What matters most when investing? For the purposes of these articles, I assume that readers need no reminder of the basic checklist of investing: to start early, to maximise allowances, keep topping up regularly, and to keep costs down. Then comes the key decision – what to invest in. The main driver of portfolio risk and return is not which stocks or equity funds are within a portfolio, but what the proportion is between higher risk-return assets such as equities, and lower risk-return assets such as shorter duration bonds. Put simply, whether to invest 20%, 60% or 100% of a portfolio in equities, will have a greater impact on overall portfolio returns, than the selection of shares or funds within that equity allocation. For example, when making spaghetti Bolognese, the ratio between spaghetti and Bolognese impacts the “outcome” of the overall meal, more than how finely chopped the onions are within the Bolognese recipe. While this may seem obvious, it gets lost in all the noise and news that focuses on hot stocks, star managers and performance rankings. For those that want to back up common sense with academic theory, the academic articles most referenced that explore this topic are Brinson Hood & Beebower (1986), Ibboton & Kaplan (2000), and Ibbotson, Xiong, Idzorek & Cheng (2010), all referenced and summarised in my book. Building a multi-asset portfolio to an optimised asset allocation to align to a particular risk-return objectives sounds like hard work and it is. That’s why multi-asset funds exist. The rise of multi-asset funds As investing becomes more accessible to more people, there is less interest in the detail of how investments work and more interest in portfolios that get people from A to B, for a given level of risk-return. After all, there are fewer people who are interested in the detail of how engines work than there are who are interested in how a car looks, how it drives and what they need it for. There is nothing new about multi-asset funds, indeed one could argue that the earliest investment trust Foreign & Colonial Investment Trust, founded in 1868, invested in both equities and bonds "to give the investor of moderate means the same advantages as the large capitalists in diminishing the risk by spreading the investment over a number of stocks”. In the unit trust world, managed balanced funds have been around for decades. I would define a multi-asset fund as a strategy that invests across a diversified range of asset classes to achieve a particular asset allocation and/or risk-return objective. They offer a ready-made “portfolio within a fund” thereby enabling a managed portfolio service for the investor from a minimum regular investment of £25 per month. . In this respect, multi-asset funds help democratise investing, and make the hardest part of the investor’s checklist – how to construct and manage a diversified portfolio. The different types of multi-asset fund available is a topic in itself. The ability for investors to select a multi-asset fund for a given level or risk-return characteristics for a given time frame is one of the most straightforward ways to implement a strategy once that has been aligned to a given set of objectives. Multi-Asset Fund or ETF Portfolio? The main advantage of a ready-made multi-asset fund is convenience. Asset allocation, and portfolio construction decisions are made by the fund provider. The main advantages of an ETF Portfolio are timeliness, cost and flexible. ETF Portfolios are timely. You can adjust positions the same day without 4-5 day dealing cycles associated with funds – an important feature in volatile times. ETF portfolios are good value. You can construct a multi-asset ETF portfolio for a lower cost than even the cheapest multi-asset fund. ETF Portfolio are flexible – you can tilt a core strategy to reflect your views on a particular region (e.g. US or Emerging Markets), sector (e.g. healthcare or technology), theme (e.g. sustainability or demographics), or factor (e.g. momentum or value), to reflect your views based on your research. Conclusion Setting the right objectives to meet a target financial outcome, such as funding future retirement, university fees, or creating a rainy day fund is the primary consideration when making an investment plan. Getting the asset allocation right – choosing a risk profile – in a way best suited to deliver that plan is the second most important decision. Finding a straight forward to deliver that risk-return profile, by building your own ETF portfolio or using a ready-made multi-asset index fund, is the final most important step. All the while, it makes sense to stick to the investing checklist: to start early, keep topping up, and keep costs down.

In this series of articles, we look at some of the key topics explored in my book “How to Invest With Exchange Traded Funds” that also underpin the portfolio design work we do for discretionary managers and financial advisers.

From space pens to pencils There’s a famous story, probably an urban myth, about NASA spending millions of dollars of research to develop a space pen whose ink could still flow in a zero gravity environment. When the Russians were asked whether they planned to respond to the challenge to enable their cosmonauts be able to write in space, they answered “We just use a pencil.” Sometimes sensible and straightforward answers to problems prove more durable than more elaborate and costly alternatives. The same could be said of investments. The quest for high-cost star-managers in the hope of alchemy, is under pressure from low-cost index funds that get the job done, by giving low cost, transparent, and liquid exposure to a particular asset class. How an active stock picker became a passive enthusiast I spent my early years in the City working for active managers. My job was to pick stocks based on proprietary models of those companies’ operating and financial models. I was fortunate enough to work in a very successful hedge fund, whose style was “true active”: it could be highly concentrated on high conviction stocks, it could be long or short a stock or a market, it could (but didn’t) use leverage. If you enjoy stockpicking, as I did, working for a relatively unconstrained mandate was at times highly rewarding, at times highly stressful and always interesting. Investors, typically large institutions, who wanted access to this strategy, had to have deep pockets to wear the very high minimum investment, and the fund was not always open for new investors. It certainly wasn’t available to the man on the street. Knowledge gap entrenches disadvantage When I started my own family and started investing a Child Trust Fund I became all too aware of the massive disconnect and difference between the investment opportunities open to hundreds of institutional investors and those available to millions of ordinary individual retail investors. I was staggered and rather depressed to see how few people in the UK harness the power of the markets to increase their long-term financial resilience. Of the 11m ISA accounts held by 30m working adult, only 2m are Stocks and Shares ISAs. The investing public is a narrow audience. The vast majority is put off from learning to or starting to invest by complexity, jargon and unfamiliarity. Casual conversations with people from all walks of life showed that whilst they may fall prey to some scheme that promised unrealistic returns, they were less inclined to put a “boring” checklist in place to contribute to their own ISA or Junior ISA, perhaps unaware that this could be done for less than the cost of a coffee habit at £25 per month. The lack of knowledge on investing was nothing to do with gender, age or education. It was almost universal. People either knew about investments or they didn’t. And that knowledge was usually hereditary. And it entrenches disadvantage. Retail investments need a shake up Looking at the retail fund industry, it was clear that there wasn’t much that was truly “active” about it. Most long-only retail managers hugged benchmarks for chunky fees that befitted their brand or status (now known as “closet indexing”). Until recently, the bulk of personal finance pages and investment journalism was more about a quest for a handful of “star managers”, in whatever asset class, who were ascribed the status of an alchemist, that investors would then herd towards. It seemed like the retail fund industry was focused on solving the wrong problem: on how to find the next star manager, rather than how to have a sensible, robust diversified portfolio. By contrast, in the US, there has always been a higher culture of equity investing (New York cabbies talk more about stocks than about sport, in my experience). So I was fascinated to read about the behavioural science that underpinned the roll out of automatic enrolment in the USA in 2005 where investors who were not engaged with their pensions plan were defaulted into a Target Date Fund – a multi-asset index fund whose mix of assets changes over time, according to their expected retirement date. I also read about the mushrooming of so-called “ETF Strategists”, investment research firms that put together ultra-low cost managed portfolios for US financial advisers built entirely with Exchange Traded Funds. Winds of change Conscious of these emerging trends, it seemed that mass market investing in the UK was about to enter a period of structural change: namely with the ban of fund commissions (Retail Distribution Review), and the launch of automatic enrolment, as well as other planned “behavioural finance” interventions to improve savings rates and financial capability. So in 2012, I set up my own research firm to see what, if any, of that experience in the US might apply in the UK. We work with asset managers to develop low-cost multi-asset investment strategies for the mass market, constructed with index-tracking funds and ETFs. It is bringing the rather dry science of institutional investing into the brand-rich and personality-heavy world of personal investing. Why index investing? I try and avoid the terms active and passive and will explain why. For most people, a multi-asset approach using index funds makes sense. This can be called “index investing”. Surprisingly, one of it’s biggest supporters is Warren Buffett. “Consistently buy a low cost…index fund. I think it’s the thing that makes the most sense practically all of the time…Keep buying through thick and thin, and especially through thin.” (Warren Buffet, Letter to shareholders, 2017) In this series of articles, I share some of the experience I have had in developing investment strategies and products for asset managers built with index funds and ETFs. I look at the concepts underpinning multi-asset investing, focus on the importance of getting the asset allocation right for a given objective, summarise my view on the active vs passive debate (and attempt to clarify some terms), as well as some practical tips on building and managing your own portfolio. Each of the articles can be explored more deeply in a book I wrote with my former colleague and co-author Shweta Agarwal on How to Invest with Exchange Traded Funds: a practical guide for the modern investor |

ELSTON RESEARCHinsights inform solutions Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Company |

Solutions |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed