|

Mainstream platforms have been slow to adopt fractional trading. This has hampered the adoption of ETFs within MPS. With many more index funds available, it's become less of an issue, according to Henry Cobbe, Head of Research at Elston Consulting.

Read the full article in ETF Stream ETF Stream interviews up-and-coming fund selectors about breaking into the industry, how experiences have shaped their investment approach and their biggest influences in investing and beyond.

Read in full [5 min read, open as pdf]

CPD Webinar: Is Active Management a Zero-Sum Game? [5 min read, open as pdf]

[3 minute read, open as pdf]

In this article for IG, Hoshang Daroga CFA, Investment Director at Elston Consulting, looks at the easing of Covid-19 restrictions in China.

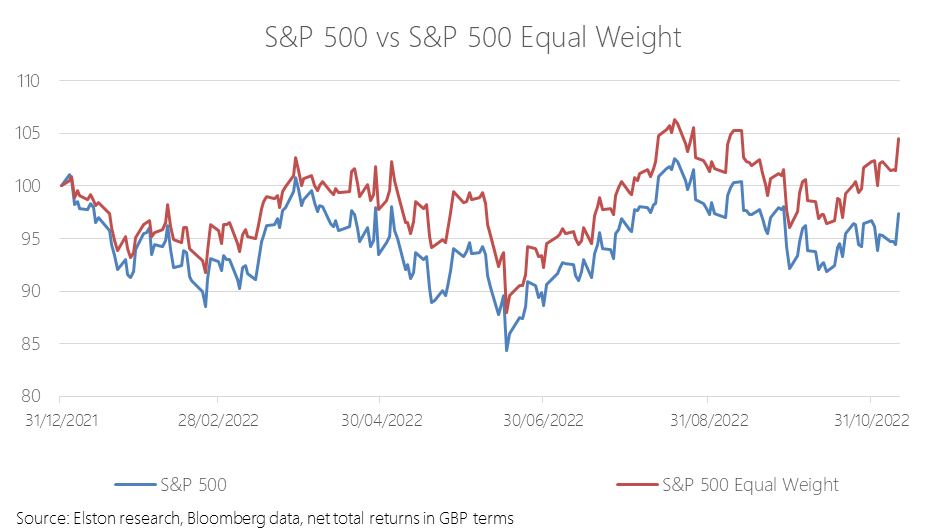

Read in full In this article for IG, Henry Cobbe explores looks at an alternative approach to US indices.

Read in full [3 min read, open as pdf]

[3 min read, open as pdf]

In this article for IG, Elston's Andrea Acimovic explores the paradox of the clean energy revolution.

Read in full In this article for IG, Jackie Qiao, Head of Fund Research at Elston Consulting, discusses the value of holding gold in times of market stress.

Read in full In this article for IG, Elston's Andrea Acimovic explores opportunities in the ESG space.

Read in full In this article for IG, Hoshang Daroga, CFA, Investment Director at Elston Consulting, explores whether and how to add back bond exposure.

Read in full [3 min read, open as pdf]

[3 min read, open as pdf]

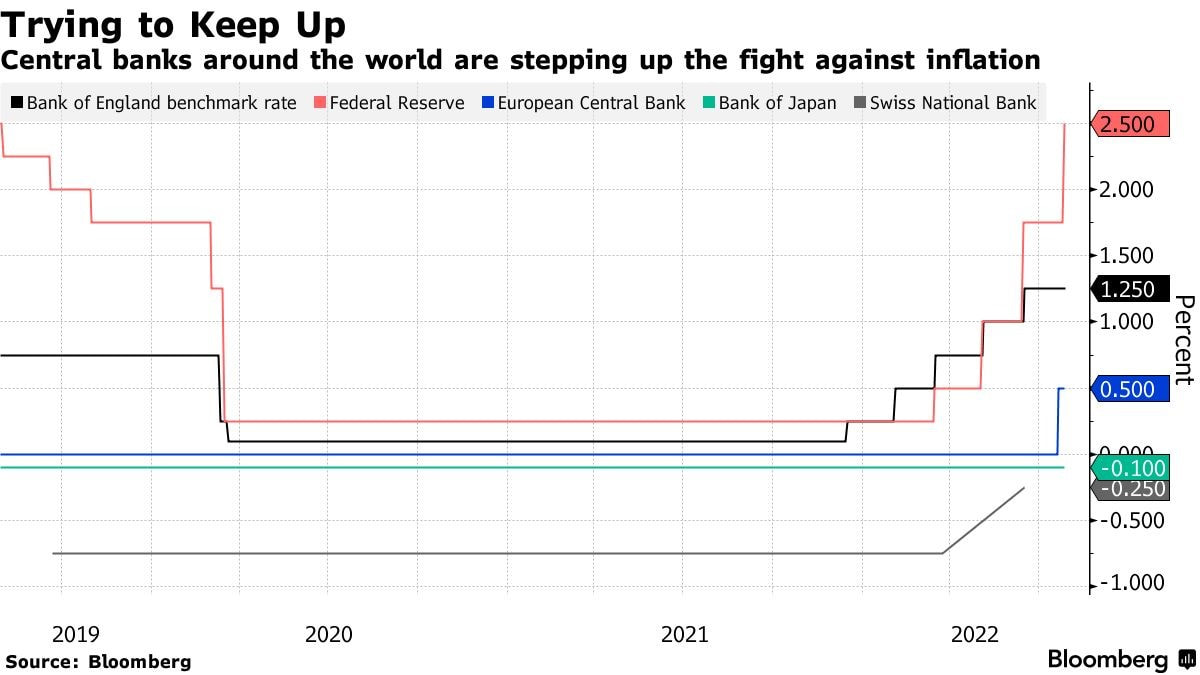

On 4th August, the Bank of England raised rates by 0.5%, the largest single increase since 1995. This followed the US Federal Reserve raising rates by 0.75% at the end of July. While these rate rises may or may not bring inflation under control, the risk they pose to growth is considerable. We consider the ways in which investors can use ETFs to build defensive resilience as an alternative to low-yielding cash or bonds. The costs of investing compound and have a negative impact on your ultimate return. Henry Cobbe is interviewed by Investor's Chronicle.

Read in full [5 min read, open as pdf]

Even before the Russia/Ukraine war and sanctions, Covid policy stimulus, rapidity of the post-Covid restart, supply-chain disruptions and the energy crisis have stoked up inflationary pressure and we are in for a bumpy ride. While we are not yet past the peak, it takes years, not months, to tame inflation, so it makes sense to adapt portfolios for an inflationary regime. To understand asset class behaviour there is not much use looking at the last 10 or 20 years. That era has been characterised by falling interest rates and low inflation. Instead we have to go back to the history books and understand how asset classes behaved in the 1970s inflation shock and the subsequent period of rising interest rates and rising inflation. From studying academic research on that era, we draw three key conclusions: firstly, inflation protection can be achieved by owning the assets that benefit, rather than suffer, from inflation. Secondly, that different asset classes have different inflation-protective qualities over time. Finally, that liquidity is key so that there is flexibility to alter and adjust your portfolio. Equities: the long-term inflation hedge Equities provide the ultimate “long-term” inflation hedge – companies that make things that you always need and have pricing power can keep pace with or beat inflation. Within equities, studies show that a bias towards value, away from growth, outperforms during an inflationary regime. This is because of something known as “equity duration”, which basically means that companies that deliver earnings and dividends on a “jam today” basis, are more valuable than companies that are expected to deliver earnings and dividends in the very distant future on a “jam tomorrow” basis. You can access a Value ETF very simply by using factor-based ETFs, such as IWFV (iShares Edge MSCI World Value Factor UCITS ETF). But given that investors are likely to have equities in their portfolios already and therefore have long-term protection in place, how do you achieve inflation-protection for the bumpy ride over the short- and medium-term? Owning the problem Inflation-hedging can be described as “owning the problem”. Worried about rising oil, gas and petrol prices? Own an Energy ETP like AIGE (WisdomTree Energy ETP). Worried about rising wheat prices? Own an Agriculture ETP like AIGA (WisdomTree Agriculture ETP). Worried about rising rail-fares? Own an infrastructure ETF like GIN (SPDR Morningstar Multi-Asset Global Infrastructure UCITS ETF). Worried about rising rents? Own a property ETF like IWDP (iShares Developed Markets Property Yield UCITS ETF). Worried about rising household bills? Own a Utilities ETF like UTIW (Lyxor MSCI World Utilities TR UCITS ETF). By owning the assets that benefit, rather than suffer, from inflation, you can incorporate inflation-protection into your portfolio. These assets are referred to as “liquid real assets” as their value is positively related to inflation. They can be accessed in liquid format by using exchange traded products (ETPs) keeping your portfolio flexible to enable future adjustments as time goes on. Interestingly, real assets respond to inflation in different ways over different time frames. The study from the 1970s looked at the correlation of asset classes over time from the start of an inflation shock. It found that Commodities provided near-term inflation protection for the initial five or so years of inflation shock, but then moderated as supply-side solutions came-through. Infrastructure and Property provided medium- to long-term inflation protection but were vulnerable in the near-term to rising market risk associated with the break-out of inflation. Inflation-linked bonds – as the name suggests – provide inflation protection, if held to maturity. But in the short-term they can decline materially, as they are highly sensitive to increases in interest rates which are typically associated with inflation-fighting central bank policy. So while inflation-linked bonds like INXG (iShares GBP Index-Linked Gilts UCITS ETF) reduce inflation risk, they increase interest rate risk. By introducing some interest-rate hedging by owning assets whose interest rates go up when the Fed raises rates, like with FLOS (iShares USD Floating Rate Bond UCITS ETF GBP Hedged), this can be mitigated. Gold Gold is also a traditional real asset inflation-hedge: it preserves its value (purchasing power) over millennia, and is a classic “risk off” asset that can help protect a portfolio in times of market stress. Some critics of holding physical gold argue that is produces no income and therefore has no intrinsic value or growth. That may be so, but imagine you were a time-traveller – it’s the only money that you could use in any era going back to biblical times. It holds its value in inflationary and even in hyperinflationary times. From a portfolio perspective, it always makes sense to have some exposure both as a real asset, a shock-absorber and as an uncorrelated diversifier. Physical gold tends to outperform gold miners, in the long-run, and can be accessed at lower cost. There are plenty of low-cost physical gold ETPs to choose from. Bringing it all together We believe that a layered approach to inflation-hedging makes sense because of the different inflation-protection qualities of different asset classes over time. Within equities this means pivoting equity exposure towards a Value/Income bias. Within bonds, this means reducing duration and/or substituting nominal bonds with liquid real assets exposure as a potential alternative (subject to relevant risk controls). We have incorporated a range of higher risk inflation-protective asset classes, such as commodities, gold, infrastructure and property, medium-risk like lower duration inflation-linked bonds and lower risk rate-sensitive assets, such as floating rate notes to create a diversified Liquid Real Assets Index strategy that aims to deliver exposure to inflation-protective asset classes, while delivering an overall portfolio volatility similar to Gilts. This makes the strategy a potential alternative to traditional (nominal) bonds exposure that will continue to struggle in an inflationary regime. Summary For those wishing to isolate and target specific inflation-protective exposures, there is no shortage of choice for highly targeted inflation-hedging strategies. Adapting portfolios for inflation is key to ensure resilience in an inflationary regime. And while it may feel a bit late to get started, it’s better late than never. Find out more about our All-Weather Portfolio of ETFs for UK investors. Find out more about our Permanent Portfolio of ETFs for UK investors. See all our Research Portfolios Dave Baxter and Henry Cobbe discuss how to sort through the thousands of funds available, and the pros and cons of different options.

Access the podcast |

ELSTON RESEARCHinsights inform solutions Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Company |

Solutions |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed