|

Most of us realise that worrying is irrational and counter-productive. Yet we can’t seem to stop ourselves, and research consistently shows that we worry about money and financial issues more than just about anything else. CARL RICHARDS is a financial adviser, writer and podcaster who specialises in behavioural finance. Carl is from Utah but is currently living in New Zealand. He says there are two simple questions we should ask ourselves whenever we find ourselves fretting about something:

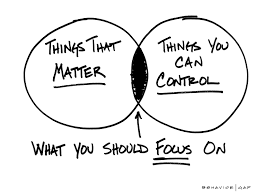

If the answer to either question is No, we should be tough with ourselves and stop worrying about it. In this interview, Carl talks about our tendency to worry about the wrong things and the danger of perfectionism. He also discusses the importance of changing our attitude towards risk and volatility. Carl, you’re renowned for your sketches for the New York Times, which illustrate simple, but important, concepts that people need to understand when thinking about money. Perhaps your best-known sketch is about the need to focus on things that matter and that we have control over — and stop worrying about everything else. How did that sketch come about? That’s one of my favourite images and it seems to be one of the most popular. The story behind it was that my son, who was ten at the time, was playing lacrosse. My Mom came to watch. It was a beautiful, sunny fall day, with a crisp blue sky. It was a great day for a father to be watching one of their kids do something cool, and it should haver been an amazing day for my Mom.

But I could see as she walked to the game, like a hundred metres away, that something was wrong. She sat down and I said, “Mum what’s wrong?” She said, “Oh, nothing,” and I said, “No really, what’s wrong?” She said, “The dollar. I’m just so worried about the dollar. It could collapse.” OK, my Mom, as far as I’m concerned, controls the universe, but she has no control over what happens to the dollar. So we started talking about that intersection of these two circles — things that matter and things that you can control. Because if it doesn’t matter, why are you worried about it? And if you can’t control it, why are you worried about it, other than to plan around it? If we can think about the intersection of things that both matter and that we can control, that’s really where we should focus, because that’s what will make a difference. In your experience as an adviser, how much time and effort do people spend worrying about things that either don’t matter, or that they can’t do anything about? I think the majority of an investor’s time, like the majority of a human’s time, is spent worrying about things that either don’t matter or that we have very little control over. The good news with investing, and with wealth management more broadly, is that if you were to make list of all the things that actually mattered, most of them are things we have control over — for example, asset allocation and our behaviour. There is one noticeable thing that matters a lot but that we do not have control over, and that’s our return, in other words, the markets. We spend 80% of our time talking and worrying about the one thing that we can’t control. I’m just suggesting that we should maybe flip that a little bit. It doesn’t mean we should totally ignore the markets. I’m just saying, why don’t we spend a little bit more time on the things we do have control over that also matter? It’s very difficult not to worry, though, when there’s extreme market volatility and stock prices are falling fast. That’s when having a financial adviser you can talk to really helps, isn’t it? Yes, I think it is really important for the adviser to talk to the client about the nature of the financial markets, and to make sure the client understands the words you’re using. Often the industry, and even really good financial advisers, will use words like risk and volatility and assume that everybody will know what they mean. But most people don’t know what they mean. I know I wouldn’t if I weren’t in this industry. As a client, the one thing I think you should feel absolutely sure you can you say to your adviser is, “Hold on. Back up and explain that.” Any good adviser will appreciate it, and if they don’t appreciate it, find a different one. It makes a lot of sense just to stop, if you don’t understand something, particularly around risk, which is incredibly important. Just pause and say, “Can you explain that to me? I want to make sure we are on the same page.” How, then, should investors think about volatility? It’s certainly scary, but it’s not the same as risk, is it? You should view volatility as risky in the short term, but not risky in the long term. Volatility is just, underneath, a measurement of standard deviation, which means, how much something wiggles. Stocks wiggle more than bonds, bonds wiggle more than cash. Short-term volatility is a measure of how much something wiggles in the short term. You just have to decide how to deal with that. If you’re going to have a portfolio that is designed to meet your goals, it requires you to take a certain level of risk. The level of risk determines how much it’s going to wiggle in the short term, and you just have to decide how you’re going to handle that. There’s a whole bunch of tricks and techniques you can do to help you ignore it, but if you’re not paying attention to it in the first place you don’t have to deal with it, so that may be a hint. Very often our attitude to risk is governed by our past experiences — particularly recent experiences. How conscious are you of that as a financial planner? I feels to me like one of the big mistakes we make as humans is what the academics would call recency bias. We look at the recent past and we project that indefinitely into the future, particularly if the recent past has been something really negative. But even if our recent experience has been really good, we can make some major mistakes that way too. You think, for example, “I’ve had a bonus every year in January for the last three years and we’re thinking about buying a new house. Maybe we could buy a more expensive house because that bonus is around the corner.” And then you don’t get the bonus, and it wreaks havoc. I think we’re really good at doing this. It happens all the time, and it’s something we need to check. But what can you do actually do about it? It’s not easy, is it? No, it’s not easy. The only solution I know to that problem is just to extend your view of recent past. Right now, in the Twitter age, the recent past is often, like, three minutes! It really helps if we can extend our view of the recent past and consider, “Oh remember, just five years ago that happened.” Another way to deal with this problem is to record how we feel about events, particularly when we’re really scared and nervous and we want to sell, and we get walked in off that ledge by a financial adviser. At that moment it can be really useful to record how we’re feeling, to remind ourselves in the future what it’s like. I think the ability to forget negative experiences in the recent past to discount negative experiences in the recent past has kept us alive as a species. No one would run a second marathon, and I’ve been told by my wife that nobody would have a second child if they could remember the pain of having the first one. We discount that really quickly. So just reminding ourselves of the pain, writing a note to ourselves, can be incredibly valuable. You’ve written several times about the dangers of perfectionism, and why our desire to have everything “just so” can hold us back in our financial lives. Why do you think it’s such a problem? There is a really unhealthy focus on the perfect — finding the perfect investment, building the perfect portfolio. Perfect really is the enemy of the good, especially as we don’t know what perfect is beforehand, and we’re guessing anyway. I think the investment process only matters to the degree that it’s going to influence our behaviour. Your portfolio may not be the most efficient thing on the planet, but if it will helps to solve your behaviour, then it’s good enough. It’s like what Jack Bogle says about index funds — there may be investment solutions that are better than this, but the ones that are worse are infinite. Of course, the other problem with focusing on the finer detail is that you neglect the bigger picture. Right. I can’t tell you how many times people will send me questions like, “What is the ultimate emerging market small-cap fund?” It might represent 3% of their portfolio and they want to spend lots of time on it. In the meantime, perhaps they haven’t got their money invested, or they didn’t fund your retirement account this year. Remember the old story of the doctor having a patient continually arguing over which medicine to take for high blood pressure. The doctor finally said, “Wait, you still smoke!” I think arguing about asset allocation and focusing on the specific investments underneath, trying to get everything perfect, really misses the point. Investors, and indeed financial professionals and commentators, are often confused by the fact that Vanguard provides actively managed funds.

Vanguard is, of course, virtually synonymous with passive investing. It was Vanguard’s founder, Jack Bogle, who launched the first index fund for retail investors in the mid-1970s, and who has since became the most vociferous critic of active management. Yet not only does Vanguard offer active funds, it also (at least here in the UK) enthusiastically promotes them. It’s not about active and passive, Vanguard’s marketing message goes; it’s all about cost. To a large extent, that’s true. As research by Morningstar and others has consistently shown, cost is the single most accurate predictor of future fund returns. Certainly, Vanguard’s active fund fees are generally considerably lower than those of its rivals. But, given the choice of an active Vanguard fund and a passive one, which should you go for? The investment author Andrew Hallam conducted research into this question in March 2015. He looked at the performance of Vanguard’s equity and bond funds, across seven different categories, over the previous ten years. In some categories, Hallam found, the active funds produced the higher returns (particular in international equities). But, overall, Vanguard’s index funds beat the active funds by 0.71% per year. Now, 71 basis points might not sound like a great deal, but when that figure is compounded over several decades, it can add up to a substantial amount. Someone else who has looked at this issue closely is the financial adviser and author Mark Hebner. In June 2016 Hebner analysed the performance of all 60 of Vanguard’s US-based active funds which had a track record of at least ten years. The fees, he confirmed, were substantially lower than the industry average. Vanguard charged an average of 0.36% for its equity funds and 0.21% for its bond funds. Hebner then looked at turnover ratios. The average was 40% for equity funds and 90% for bond funds; in other words, a typical holding period was between one and two-and-a-half years. These figures are much more in line with the industry average and imply that Vanguard’s active managers tend to make decisions based on short-term outlooks. Although transaction costs aren’t included in the headline fee, they are borne by the investor and have a significant on net returns. The next question Hebner addressed was whether Vanguard investors could expect superior performance in return for the premium they were paying for active management. This is what he found:

This distinction between repeatable skill and random chance is very important. By random chance alone, you would expect either one or two of the funds analysed (1 in 40 to be precise) to produce what’s called statistically significant alpha. Put another way, no more of Vanguard’s funds outperformed than you would expect just from random chance. “In general,” Hebner concluded, “Vanguard has not demonstrated that their process of hiring the best analysts and managers and implementing their investment strategies is superior to anyone else. To say they apply a unique process to just two of their investment strategies seems very unlikely.” So let’s go back to our original question: Are Vanguard’s low-cost active funds a good bet? They are, as with all active funds, most definitely a bet. But a good one? Well, because the fees are lower, using an active fund from Vanguard is a better bet than choosing a typical average fund. But the bottom line is that markets are efficient. All active management, low-fee or otherwise, is a zero-sum game before costs and a negative-sum game after costs. Not even Vanguard, for all the good that it’s done for investing and for investors, is immune to those brutal facts. Do Vanguard’s active managers possess skill and insight or have resources at their disposal that active managers that all the other big fund houses don’t? The figures don’t lie, and the figures suggest they don’t. |

ELSTON RESEARCHinsights inform solutions Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Company |

Solutions |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed