|

[5 min read, open as pdf]

Henry Cobbe explores the challenges of building portfolios for retirement and also sizing "right" allocation to UK Equities.

Read the article / access the podcast Markets don't stand still. Should portfolios?

We explore two apparently opposing schools of thought. Read the full article in FT Adviser [5 min read]

In the ultra-low interest rate era that followed the financial crisis, there was little incentive to allocate to cash. But should the promise of a now-meaningful risk-free return prompt investors to switch away from equities? Read the full article in FT Adviser These rules of thumb stand the test of time. Investor's Chronicle interviews Elston's Henry Cobbe.

Read in full [3 min read, open as pdf]

The costs of investing compound and have a negative impact on your ultimate return. Henry Cobbe is interviewed by Investor's Chronicle.

Read in full [5 min read, open as pdf]

Some 18 year olds will have their Child Trust Fund maturing. Depending on how their parents had invested it, that could mean a lot or a little start to adult life. Our Head of Research, Henry Cobbe, provides some suggestions as regards next steps for an 18 year old with £29,000 to invest First of all – I’m sure you’ve done a big thank you to your parents for having set up, and topped up your CTF to grow it thus far! Everyone had the same starting point with CTFs, but it’s the decisions that your parents made that has determined your portfolio thus far. You should ask your parents’ adviser to help you get started, but if you really want to manage your own portfolio for now, rather than take advice, I would encourage you to make a straightforward three-step plan. 1. Choose your platform Firstly, decide on a platform. Interactive Investor’s flat-fee account is great for much larger pots, but your pot size means it’s much of a muchness between them and the other well-capitalised providers like Fidelity, AJ Bell and Hargreaves Lansdown. For a detailed analysis of platform fees, take a look at comparefundplatforms.com Using their tool, and assuming £29,000 lump sum ISA, £50 per month top up into 2 funds and no switches (buy and hold!), a like for like comparison suggests Interactive Investor 0.32% annual fees, AJBell 0.35%, Fidelity 0.35% and Hargreaves Lansdown 0.45%. Take a look at each website, decide which you find to be most helpful, and easiest to navigate. Customer service is important too, so try calling their helpdesks and see you find most helpful! 2. Choose your funds Secondly, decide on which funds, if you have a specific amount that you would ear-mark for the property deposit, and you expect that it’s in ten years’ time, you could consider using a target date fund, like Vanguard Target Retirement 2030 Fund Acc (0.24% OCF) or Vanguard Target Retirement 2035 Fund Acc (0.24% OCF) for that portion and ear mark that as your “deposit pot”. This means that as you get towards the target date, the investment strategy becomes less risky. That way the pot earmarked for your deposit is less exposed to a market shock if there is one in the run-up to you wanting withdraw funds for your deposit. For the remainder of your pot, as you’re lucky enough to have youth on your side, you have what’s called high “capacity for risk” in economic terms (not related to your behavioural/emotional “attitude to risk”), so can afford to take risk for long-term investments as the necessary flipside of returns. So for the remainder have a look at low cost global equity index funds such as:

3. Keep topping up Finally – and most importantly – heed the words of Warren Buffet in his advice to retail investors: “keep topping up through thick and thin, and especially through the thin”. The minimum fund subscription is £25 per month, so set up a regular investment plan into your chosen funds. The power of tax-free compounding is a marvel to behold. If markets have a wobble and you have spare cash, that can be a great time to top up with whatever you can afford. Lump sum or phased in? Markets are quite volatile at the moment so once you’ve got the money into your ISA, make a plan to invest into your chosen funds proportionally in say three or four stages over the rest of the year. That way you are “averaging in” to the market, rather than either getting very lucky (buying at a market low), or very unlucky (buying at a market high). Whilst in the long-run (say 30 years) it won’t matter (according to academia), it does make a difference to how you feel about taking the plunge, and can help remove a lot of worry. Set a date for review Make a plan as to when you will check in to your account – monthly, quarterly or annually. You would also need to rethink your strategy if your situation changes, or if your goals change. Whilst young and care-free you are probably right in your analysis that you may not need an adviser at this stage. But also put a date in your diary to speak to one when you’re any or all of 30, in a marriage/civil partnership, or starting a family. A good financial planner will review your situation and make sure that you have all the right things in place: mortgage, will, insurance, consolidated pensions, making the most of tax allowances and a broader plan to achieve your medium and long-term financial goals, whilst squaring off key financial risks. Good luck with the start of your investing journey! Notice: Not a personal recommendation. No assessment of suitability. Personal opinions expressed do not reflect the views of the author’s employer. Self-directed investors should read the terms and conditions and risk warnings of their selected platform, together with the KIID of any fund they select. In this podcast, Henry Cobbe explores behavioural biases in an interview with Investor's Chronicle.

Access the podcast [5 min read, open as pdf]

In our 2022 outlook, we explained why inflation will remain hotter for longer and will settle above pre-pandemic levels. Advisers should consider how to adapt portfolios for inflation across each asset class – equities, bonds and alternatives. Research demonstrates how different asset classes exhibit different degrees of inflation protection over different time-frames. Equities therefore provide a long-term inflation hedge.

In this article, we explore how to adapt portfolios for inflation within and across each asset class: Equities, Bonds and Alternatives. For full article, read as pdf With thousands of funds available, learn how to sort the wheat from the chaff. Elston's Henry Cobbe is interviewed by Investor's Chronicle.

Read the article Watch the video [Open as pdf]

Money market funds, and their exchange-traded equivalents “ultra-short duration bond funds”, are an important, if unglamorous, tool in portfolio manager’s toolkit. They can be used in place of a cash holding for additional yield, without compromising on risk, liquidity or cost. Money market funds are intended to preserve capital and provide returns similar to those available on the wholesale money markets (e.g. the SONIA rate that replace LIBOR). How risky is a money market fund? Money market-type funds hold near-to maturity investment grade paper. Their weighted average term to maturity is <1 year. They therefore have very low effective duration (the sensitivity to changes in interest rates). Compare gilts which are seen as a low-risk asset relative to equities. The 10-11 year duration on UK gilts (all maturities) means they carry a higher level volatility compared to cash (which has nil volatility). On the flip side, their longer term also means they have higher risk-return potential relative to cash and ultra-short bonds. By contrast, money market type funds have some investment risk as they hold non-cash assets, but given their holdings’ investment grade status, short term to maturity and ultra-short effective duration, they exhibit near-nil volatility. Platform cash, fixed term deposit or money market fund From a flexibility perspective and a value for money perspective, there's a clear rationale to hold money market funds, rather than platform cash or a fixed term deposit. Our Money Markets fund research paper that looks at 4 low cost money market funds sets out why Why does the fund structure make sense? Find out more in our CPD Webinar on Introduction to Collective Investment Schemes [3 min read, open as pdf]

The active vs passive debate is nothing new: the first index fund was launched in 1976 to track the S&P 500. In 1991, Nobel prize winner, William Sharpe (of Sharpe ratio fame), wrote a paper on “The Arithmetic of Active” setting out some of the clichés articulated by active managers, and why, in his view, it’s a zero sum game. Definition terms is key Whenever the active vs passive debate kicks off it’s always important to define terms. If referring to an asset allocation process, we prefer the terms static and dynamic and that’s got nothing to do with the subject of this paper or the claims by index investors that “active” is a zero sum game. Nor does the “activeness” or otherwise of hedge funds. The zero-sum game allegation relates to security selection, typically in a long-only context and therefore most relevant to managers of portfolios of securities and/or retail funds. What the Sharpe paper says Broadly speaking the Sharpe paper argues that in a closed world of active managers (stock pickers within an asset class), where the opportunity set is the index, for every “star” manager buying and holding the best performing stocks, there is a “dog” manager to whom the worst performing stocks have been sold. In aggregate, over time, this means the combined performance of both managers is the same as the index less active fees. This makes it hard for active managers to persistently outperform the index over time, which is evidenced by the SPIVA study. On this basis, using a fund that delivers performance of the index less passive fees seems like a more efficient way to gain exposure to that opportunity set. What are the implications for fund pickers The SPIVA study shows that the ability of active managers to outperform an index persistently varies from market to market depending on the efficiency of that market. For example, US and Global Equity markets fewer managers manage to outperform. For UK and Emerging Markets, active managers achieve better results. The latest SPIVA scorecard can be found here. We are not against “true active”, but the “arithmetic” is stacked against traditional long-only retail managers when it comes to persistency of alpha. Incorporating an index based approach where markets are highly efficient, and or where the availability of “true active” managers is rare. How to identify “true active” is a topic for another day!

[3 min read, open as pdf] [ 5 min read, open as pdf]

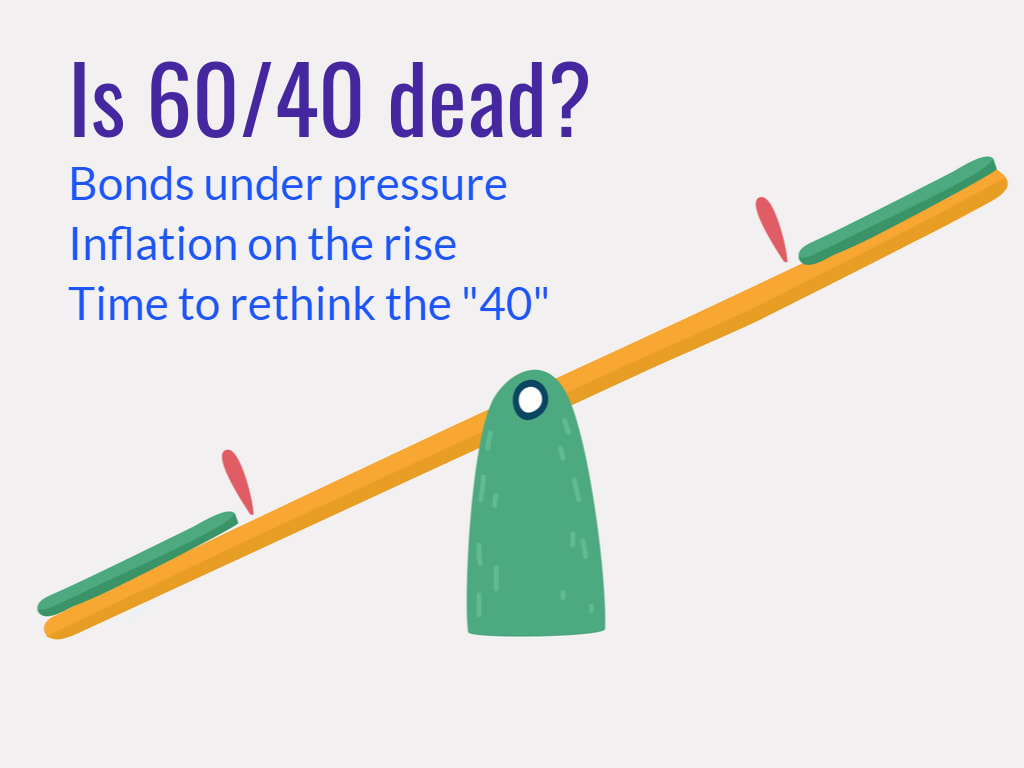

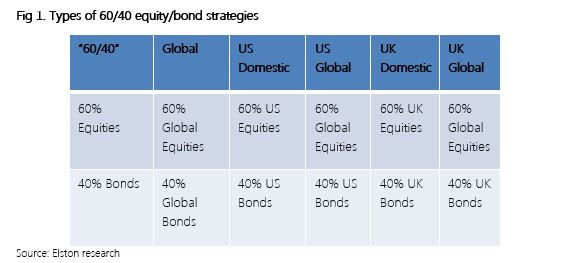

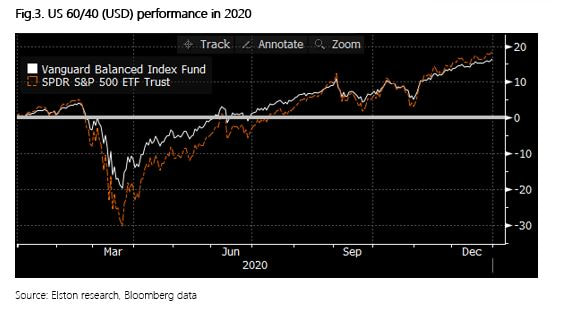

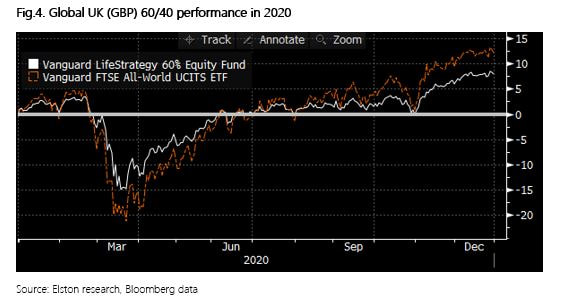

Since an article published in 2019 pointed the historic lows in bond yields, many investment firms are starting to rethink the 60/40 portfolio. This came under even more scrutiny following the market turmoil of 2020. While some affirm that the 60/40 will outlive us all, others argue against this notion. We take a look at the main arguments for and against and key insights What is a 60/40 portfolio? A 60/40 equity/bond portfolio is a heuristic “rule of thumb” approach considered to be a proxy for the optimal allocation between equities and bonds. Conventionally equities were for growth and bonds were for ballast. The composition of a 60/40 portfolio might vary depending on the base currency and opportunity set of the investor/manager. Defining terms is therefore key. We summarise a range of potential definitions of terms: Furthermore, whilst 60/40 seems simple in terms of asset weighting scheme, it is important to understand the inherent risk characteristics that this simple allocation creates. For example, a UK Global 60/40 portfolio has 62% beta to Global Equities; equities contribute approximately 84% of total risk, and a 60/40 portfolio is approximately 98% correlated to Global Equities[1]. [1] Elston research, Bloomberg data. Risk Contribution based on Elston 60/40 GBP Index weighted average contribution to summed 1 Year Value At Risk 95% Confidence as at Dec-20. Beta Correlation to Global Equities based on 5 year correlation of Elston 60/40 GBP Index to global equity index as at Dec-20. Why some think 60/40 will outlive us all. The relevance of 60/40 portfolio lies in its established historic, mathematical and academic backup. Whilst past performances do not guarantee future returns, it nonetheless provides us with experience and guidance. (Martin,2019) Research also suggests that straightforward heuristic or “rule-of-thumb” strategies work well because they aren’t likely to inspire greed or fear in investors. They become timeless. Thus, creating a ‘Mind-Gap’. (Martin,2019) In the US, the Vanguard Balanced Index Fund (Ticker: VBINX US) which combines US Total Market Index and 40% into US Aggregate bonds, plays a major role in showcasing the success of the 60/40 portfolio that has proved popular with US retail investors (Jaffe,2019). Similarly, in the UK the popularity of Vanguard LifeStrategy 60% (Ticker VGLS60A) showcases the merits of a straightforward 60/40 equity/bond approach. In 2020, for US investors VBINX provided greater (peak-to-trough) downside protection owing to lower beta (-19.5% vs -30.3% for US equity) and delivered total return of +16.26% volatility of 20.79%, compared to +18.37% for an ETF tracking the S&P 500 with volatility of 33.91%, both funds are net of fees. In this respect, the strategy captured 89% of market returns, with 61% of market risk. For GBP-based investors in 2020 the 60/40 approach had lower (peak-to-trough) drawdown levels (-15%, vs -21% for global equities) owing to lower beta. The 60% equity fund delivered total return of +7.84% with volatility of 15.12%, compared to +12.15% for an ETF tracking the FTSE All World Index with volatility of 24.29%. In this respect, the strategy captured 65% of market returns, with 62% of market risk. Why some think 60/40 has neared its end

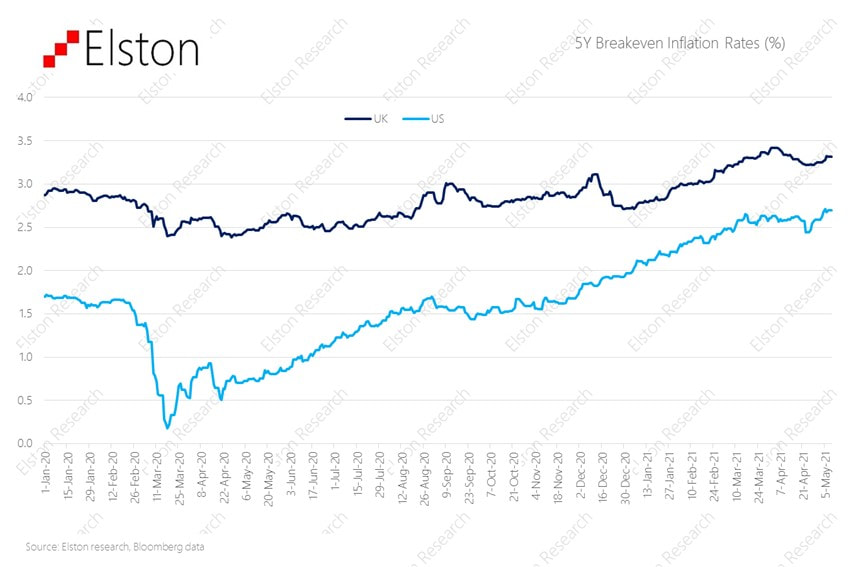

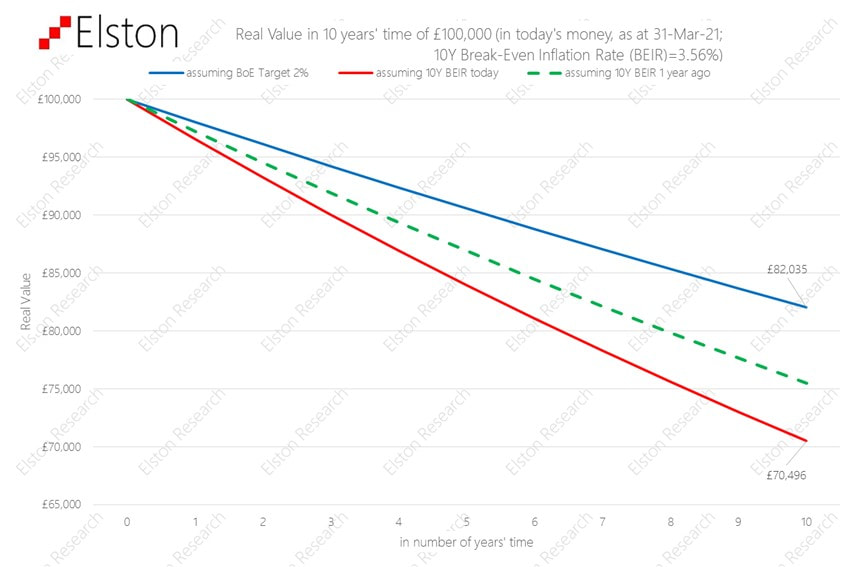

Since its inception the 60/40 portfolio, derived 90% of the risk from stocks. In simple terms, 60% of the asset allocation of the portfolio was therefore the main driver of the portfolio. Returns (Robertson,2021). This hardly a surprise given that equities have a 84% contribution to portfolio ris, on our analysis, but the challenge made by some researchers is that if a 60/40 portfolio mainly reflects equity risk, what role does the 40% bond allocation provide, other than beta reduction? The bond allocation is under increasing scrutiny now is because global economic growth has slowed and traditionally safer asset classes like bonds have grown in popularity making bonds susceptible to sharp and sudden selloffs. (Matthews,2019) Strategists such as for Woodard and Harris, for Bank of America and Bob Rice for Tangent Capital have stated in their analysis that the core premise of the 60/40 portfolio has declined as equity has provided income, and bonds total return, rather than the other way round.. (Browne,2020) Another study shows that over the past 65 years bonds can no longer effectively hedge against inflation and risk reduction through diversification can be done more adequately by exploring alternatives such as private equity, venture capital etc. (Toschi, 2021). Left unconstrained, however, this can necessarily up-risk portfolios. With bond yields at an all-time low, nearing zero and the fact that they can no longer provide the protection in the up-and-coming markets many investors query the value provided by a bond allocation within a portfolio. (Robertson,2021) Key insights While point of views might differ about 60/40 as an investment strategy, one aspect that is accepted is that the future of asset allocation looks very different when compared to the recent past. Rising correlations, low yields have led strategists and investors to incorporate smarter ways of risk management, explore new bond markets like China, create modified opportunities for bonds to hedge volatility through risk parity strategies, as well as using real asset exposure such as real estate and infrastructure. (Toschi, 2021) Research conducted by The MAN Institute summarises that modifying from traditional to a more trend-following approach introduces the initial layer of active risk management. By adding an element of market timing investors further reduce the risk, when a market’s price declines. While bonds have declined in yield, they still hold importance in asset allocation for beta reduction. Further diversifying the portfolio with an allocation to real assets has potential to provide more yield and increased return than government bonds. Summary The 60/40 portfolio strategy has established itself over many decades, it has seen investors through four major wars, 14 recessions, 11 bear markets, and 113 rolling interest rate spikes. It has proved resilience as a strategy and utility as a benchmark. Our conclusion is that 60/40 is not dead: it is a useful multi-asset benchmark and remains a starting point for strategic asset allocation strategies. But the detail of the bond allocation needs a rethink. Incorporating alternative assets or strategies so long as any increased risk can be constrained to ensure comparable portfolio risk characteristics. Henry Cobbe & Aayushi Srivastava Elston Consulting Bibliography Browne, E., 2021. The 60/40 Portfolio Is Alive and Well. [online] Pacific Investment Management Company LLC. Available at: https://www.pimco.co.uk/en-gb/insights/blog/the-60-40-portfolio-is-alive-and-well Jaffe, C., 2019. No sale: Don’t buy in to ‘the end’ of 60/40 investing. [online] Seattle Times. Available at: https://www.seattletimes.com/business/no-sale-dont-buy-in-to-the-end-of-60-40-investing/ Martin, A., 2019. The 60/40 Portfolio Will Outlive Us All. [online] Advisorperspectives.com. Available at:https://www.advisorperspectives.com/articles/2019/11/11/the-60-40-portfolio-will-outlive-us-all#:~:text=As%20two%20recent%20commentaries%20demonstrate,40%20will%20outlive%20us%20all. Matthews, C., 2021. Bank of America declares ‘the end of the 60-40’ standard portfolio. [online] MarketWatch. Available at:https://www.marketwatch.com/story/bank-of-america-declares-the-end-of-the-60-40-standard-portfolio-2019-10-15 Robertson, G., 2021. 60/40 in 2020 Vision | Man Institute. [online] www.man.com/maninstitute. Available at:https://www.man.com/maninstitute/60-40-in-2020-vision Toschi, M., 2021. Why and how to re-think the 60:40 portfolio | J.P. Morgan Asset Management. [online] Am.jpmorgan.com. Available at: https://am.jpmorgan.com/be/en/asset-management/adv/insights/market-insights/on-the-minds-of-investors/rethinking-the-60-40-portfolio/ [3 min read, open as pdf] Inflation is on the rise Easy central bank money, pent up demand after lockdowns and supply-chain constraints mean inflation is on the rise. Will Central Banks be able to keep the lid on inflation? The risk is that it could persistently overshoot target levels. It matters more over time Inflation erodes the real value of money: its “purchasing power”. If inflation was on target (2%), £100,000 in 10 year’s time would be worth only £82,035 in today’s money. But on current expectations, it could be worth a lot less than that. Real assets can help

A bank note is only as valuable as the value printed on it. This is called its “nominal value”. Remember the days when a £5 note went a long way? When inflation rises, money loses its real value. By contrast, real assets are things that have a real intrinsic value over time whose value is set by supply, demand and needs: like copper, timber, gold, oil, and wheat. Real assets can also mean things that produce an regular income which goes up with inflation, like infrastructure companies (pipelines, toll roads, national grid etc) and commercial property with inflation-linked rents. Rethinking portfolio construction Including “real assets” into the mix can help diversify a portfolio, and protect it from inflation. Obviously there are no guarantees it will do so perfectly, but it can be done as a measured approach to help mitigate the effects of inflation. The challenge is how to do this without taking on too much risk. Find out more about our Liquid Real Assets Index [5min read, open as pdf]

We agree it’s time to rethink the 60/40 portfolio. It’s a useful benchmark, but a problematic strategy. What is the 60/40 portfolio, and why does it matter? What it represents? Trying to find the very first mention of a 60/40 portfolio is proving a challenge, but it links back to Markowitz Modern Portfolio Theory and was for many years seen as close to the optimal allocation between [US] equities and [US] bonds. Harry Markowitz himself when considering a “heuristic” rule of thumb talked of a 50/50 portfolio. But the notional 60/40 equity/bond portfolio has been a long-standing proxy for a balanced mandate, combining higher-risk return growth assets with lower-risk-return, income generating assets. What’s in a 60/40? Obviously the nature of the equity and the nature of the bonds depends on the investor. US investor look at 60% US equities/40% US treasuries. Global investors might look at 60% Global Equities/40% Global Bonds. For UK investors – and our Elston 60/40 GBP Index – we look at 60% predominantly Global Equities and 40% predominantly UK bonds Why does it matter? In the same way as a Global Equities index is a useful benchmark for a “do-nothing” stock picker, the 60/40 portfolio is a useful benchmark for a “do-nothing” multi-asset investor. Multi-asset investors, with all their detailed decision making around asset allocation, risk management, hedging overlays and implementation options either do better than, or worse than this straightforward “do-nothing” approach of a regularly rebalanced 60/40 portfolio. Indeed – its simplicity is part of its appeal that enables investors to access a simple multi-asset strategy at low cost. The problem with Bonds in a 60/40 framework In October 2019, Bank of America Merrill Lynch published a research paper “The End of 60/40” which argues that “the relationship between asset classes has changed so much that many investors now buy equities not for future growth but for current income, and buy bonds to participate in price rallies”. This has prompted a flurry of opinions on whether or not 60/40 is still a valid strategy The key challenges with a 60/40 portfolio approach is more on the bond side:

So is 60/40 really dead? In short, as a benchmark no. As a strategy – we would argue that for serious investors, it never was one. We therefore think it’s important to distinguish between 60/40 as an investment strategy and 60/40 as a benchmark. We think that a vanilla 60/40 equity/bond portfolio remains useful as a benchmark to represent the “do nothing” multi-asset approach. However, we would concur that a vanilla 60/40 equity/bond portfolio, as a strategy offered by some low cost providers does – at this time – face the significant challenges identified in the 2019 report, that have been vindicated in 2020 and 2021. For example, during the peak of the COVID market crisis in March 2020, correlations between equities and bonds spiked upwards meaning there was “no place to hide”. The growing inflation risk has put additional pressure on nominal bonds. Real yields are negative. Interest rates won’t go lower. But outside of some low-cost retail products, very few portfolio managers, would offer a vanilla equity/bond portfolio as a client strategy. The inclusion of alternatives have always had an important role to play as diversifiers. Rethinking the 40%: What are the alternatives? When it comes to rethinking the 60/40 portfolio, investors will have a certain level of risk budget. So if that risk budget is to be maintained, there is little change to the “60% equity” part of a 60/40 portfolio. What about the 40%? We see opportunity for rethinking the 40% bond allocation by: We nonetheless think it is important to:

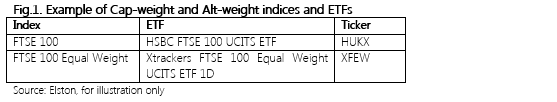

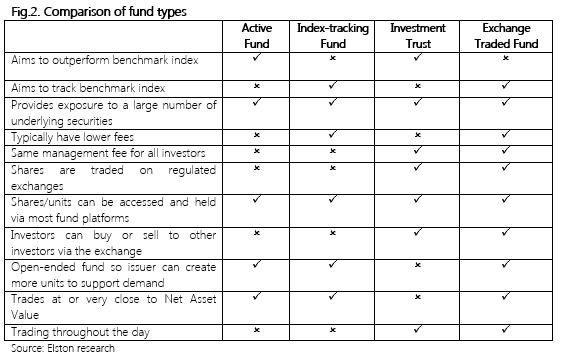

1. Rethinking the bond portfolio Whilst more extreme advocates of the death of 60/40 would push for removing bonds entirely, we would not concur. Bonds have a role to play for portfolio resilience in terms of their portfolio function (liquidity, volatility dampener), so would instead focus on a more nuanced approach between yield & duration. We would concur that long-dated nominal bonds look problematic, so would suggest a more “barbell” approach between shorter-dated bonds (as volatility dampener), and targeted, diversified bond exposures: emerging markets, high yield, inflation-linked (for diversification and real yield pick-up). 2. Incorporating sensible alternative assets Allocating a portfolio of the bond portfolio to alternatives makes sense, but we also need to consider what kind of alternatives. Whilst some managers are making the case for hedge funds or private markets as an alternative to bonds, we think there are sensible cost-efficient and liquid alternatives that can be considered for inclusion that either have bond-like characteristics (regular stable income streams), or provide inflation protection (real assets). For regular diversified income and inflation protection, we would consider: asset-backed securities, infrastructure, utilities and property. The challenge, however, is how to incorporate these asset classes without materially up-risking the overall portfolio. For inflation protection, we would consider real assets: property, diversified, commodities, gold and inflation-protected bonds. Properly incorporated these can fulfil a portfolio function that bonds traditionally provided (liquidity, income, ballast and diversification). 3. Consider risk-based diversification as an alternative strategy One of the key reasons for including bonds in a multi-asset portfolio is for diversification purposes from equities on the basis that one zigs when the other zags. In the short-term, and particularly at times of market stress, correlations between asset classes can increase, this reduces the diversification effect if bonds zag when equities zag. We would argue risk-based diversification strategies have a role to play to here, on the basis that rather than relying on long-run theoretical correlation, they systematically focus on short-run actual correlation between asset classes and adapt their asset allocation accordingly. Traditional portfolios means choosing asset weights which then drive portfolio risk and correlation metrics. Risk-based diversification strategies do this in reverse: they use short-run portfolio risk and correlation metrics to drive asset weights. If the ambition is to diversify and decorrelate, using a strategy that has this as its objective makes more sense. Summary So 60/40 is not dead. It will remain a useful benchmark for mult-asset investors. As an investment strategy, vanilla 60/40 equity/bond products will continue to attract assets for their inherent simplicity. But we do believe a careful rethink of the “40” is required. Compared to traditional retail funds, ETFs offer transparency, liquidity and efficiency [7 min read, Open as pdf] In this series of articles, I look at some of the key topics explored in my book “How to Invest With Exchange Traded Funds” that also underpin the portfolio design work Elston does for discretionary managers and financial advisers. Indexes: the DNA of an ETF An Exchange Traded Fund is an index-tracking investment fund that aims to track (perform exactly in line) with the benchmark index in the fund’s name. The index defines an ETF’s “DNA”. An index is a collective measure of value for a defined group of securities, where criteria for inclusion and weighting within that group are defined by a systematic set of rules. Indices can represent a basket of equities like the FTSE 100 Index (the “Footsie”) or a basket of bonds like the FTSE Actuaries UK Conventional Gilts All Stocks Index (the “gilts” index). Indices can be used as benchmarks to represent the performance of an asset class or exposure. ETFs aim to track these benchmark indices by holding the same securities in the same weights as the index. Whilst ETFs can be an equity fund or bond fund (amongst others) with respect to its underlying holdings and the index it tracks, the shares in those ETFs trade on an exchange like an equity. This means ETFs combine the diversification advantages of a collective investment scheme, with the accessibility advantages of a share, all at a management fee that is substantially lower than traditional active funds. These features make ETFs easy to buy, easy to switch and easy to own, revolutionising the investment process as well as reducing investment costs. Indices enable transparency ETFs are regulated collective investment schemes (often UCITS[1] schemes) that can be traded on a recognised exchange, such as the London Stock Exchange. Whereas the manager of a traditional active fund aims to outperform an index such as the FTSE 100 by overweighting or underweighting particular securities within that index or holding non-index securities, an ETF aims to deliver the same returns as the index by holding within the fund the same securities as the index in the same proportion as the index. If the index represents a basket of securities weighted by their respective size, it is a “Capitalisation-weighted index”: this is the traditional index approach. If the index represents a basket of securities weighted by a criteria other than their respective size, it is an “Alternatively-weighted” index. For example, an equal weighted index means all the securities in an index are given an equal weight. [1] UCITS: Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (the European regulatory framework for retail investment funds) ETFs track indices, and indices have rules. Index rules are publicly available and set out how an index selects and weights securities and how frequently that process is refreshed. Indices therefore represent a range of investment ideas and strategies, but codified using a rules-based approach. This makes ETFs’ investment approach transparent, systematic and predictable, even if the performance of securities within the index is not. Furthermore, ETFs publish their full holdings every day so investors can be sure of what they own. This makes ETFs’ investment risks transparent. The investment risk-return profile of an ETF is directly link to the risk-return profile of the index that it tracks. Hence ETFs tracking emerging market equity indices are more volatile than those tracking developed market indices, which in turn are more volatile than those tracking shorter-duration bond indices. As with direct shares, traditional active mutual funds and index-tracking funds, when investing in ETFs, capital is at risk, hence the value of investments will vary and the initial investment amount is not guaranteed. ETFs vs traditional funds An ETF is different to other types of investment fund in the following ways:

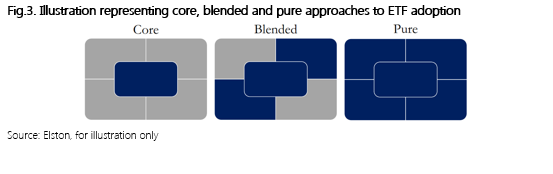

The primary advantage of ETFs is the additional liquidity that a “secondary market” creates in the shares of that ETF (meaning the ability for investors to buy or sell existing shares of that ETF amongst themselves via a recognised exchange). However it is important to note that ultimately the liquidity of any ETF is only as good as its underlying assets. Traditional mutual funds can be traded once a day and investors transact with the fund issuer who must buy or sell the same amount of underlying securities. Fund issuers have the right to “gate” funds and refuse to process redemptions to protect the interests of the broader unitholders of the fund. If this happens, there is no secondary market for shares/units in the fund. Recent examples of “gating” include UK property funds after the Brexit vote[1] and strategic bond funds as interest rates expectations rose[2]. By contrast, Exchange Traded Funds can be traded throughout the day and investors generally transact with each other via the exchange. If necessary the fund issuer must create (or redeem) more units to meet demand and then buy (or sell) the same amount of underlying securities. Whilst, the liquidity of the fund is ultimately only as good as the underlying assets, there is, however, additional liquidity in the secondary market for shares in the fund which can be bought or sold amongst investors. For example, there have been circumstances when some markets have closed, and the underlying shares aren’t traded, the ETF continues to trade (albeit a premium or discount to Net Asset Value (NAV) may appear owing to the inability of the ETF to create/redeem units when there is no access to the underlying shares) and indeed becomes a vehicle of price discovery for when the market eventually reopens[3]. As regards fees, whereas funds have different fee scales for different types of investor based on share classes available, the fees on ETFs are the same for all investors meaning that the smallest investors benefit from the economies of scale that the largest investors bring. Whilst the active/passive (we prefer the terms non-index/index) debate grabs the headlines, it is this targeted acces to specific asset classes, fee fairness and secondary market liquidity that makes ETFs so appealing to investors of any size. A summary of similarities and differences of ETFs to other types of fund is presented in the table below: [1] https://seekingalpha.com/article/3986464-investors-u-k-property-etfs-affected-9b-fund-lock [2] https://www.ft.com/content/a007d563-4454-3c92-aeaa-4d0dc64e425b [3] https://www.cnbc.com/id/41354109 From the table above, we see how, ETFs offer the combined functionality of a collective investment scheme with the flexibility and access of an exchange traded instrument. Ways to use ETFs We see three key applications for ETFs in portfolio construction: “core”, “blended” and “pure”. Using ETFs for a core portfolio means creating and managing a core asset allocation constructed using ETFs, with satellite “true active” fund holdings for each of the same exposures in an attempt to capture some manager alpha at a fund level. This enables a portfolio manager to reduce partially the overall client costs without forsaking their hope of higher expected returns from “true active” non-index fund holdings for each exposure. Using ETFs for a blended portfolio means creating and managing an asset allocation constructed using ETFs for efficient markets or markets where a portfolio managers may lack sufficient research or experience; and active funds for asset class exposures where the manager has high conviction in their ability to deliver alpha from active fund or security selection. For example, a UK portfolio manager with high conviction in UK stock picking may prefer to access US equity exposure using an ETF that tracks the S&P500 rather than attempting to pick stocks in the US. Use of ETFs for a pure ETF Portfolio means creating and managing an asset allocation constructed using ETFs entirely. For example, a portfolio manager looking to substantially reduce overall client costs without compromising on diversification is able to design a portfolio using ETFs for each asset class and risk exposure. Fig.3. Illustration representing core, blended and pure approaches to ETF adoptio Who uses ETFs and why?

ETFs are used by investors large and small to build and manage their portfolios. As well as providing low cost, diversified and transparent access to a market or asset class, the liquidity of ETFs namely that 1) they only invest in liquid securities that index-eligible and 2) the ETF can itself be bought or sold between market participants means that investors can adapt their portfolio in a timely basis, if required. Put differently traditional funds are one of the few things in the world that you can only sell back to the person you bought it from (the fund issuer), and that fund issuer has the right to say no. Furthermore, the dealing cycles for traditional funds are long. If you want to sell one to buy another, it could take 4-5 days to sell and 4-5 days to buy. An 8-10 day round trip is hardly timely. In the meantime you may be out of the market, which could dramatically impact performance, particularly in periods of extreme volatility. By contrast, ETFs are designed to be tradable on a secondary market via an exchange, and can be bought and sold between market participants on the same day without the fund manager’s involvement. This means that if investors want to alter their risk posture to respond to changing events, they can do so instantly and effectively if required. ETFs have therefore grown in popularity as a core part of institutional and retail investor’s toolkit for portfolio and risk management. |

ELSTON RESEARCHinsights inform solutions Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Company |

Solutions |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed