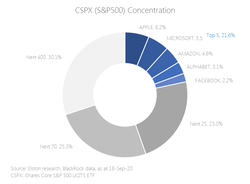

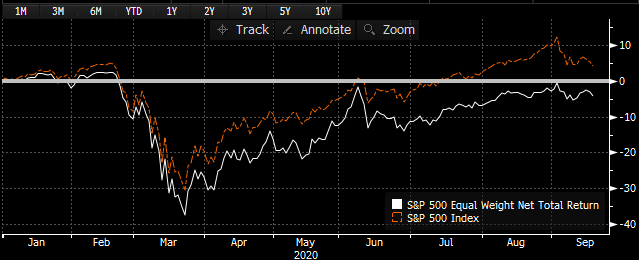

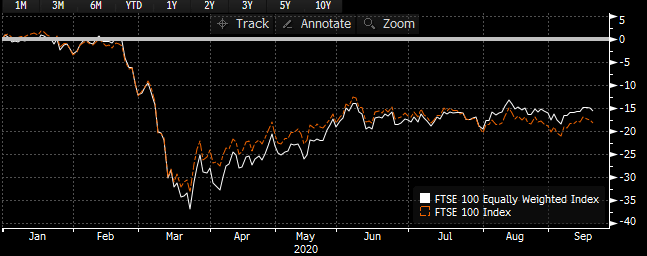

Focus on index methodology Methodology is the genetic code of an index. The rules that govern how an index is constructed determines what’s in it, at what weights, and therefore how it will perform in relation to the performance of all its components. A handful of (mainly older) indices are price-weighted indices (such as the DJIA (in the US, since 1896), FT30 (in the UK, since 1935), and Nikkei 225 (in Japan, since 1950). This means the weight of each stock in the index is determined by its price relative to the summed prices of all the constituents of the index. The bulk of the most familiar, and most tracked, indices are capitalisation-weighted indices. This means the weight of each stock in the index is determined by its (often free-float-adjusted) market capitalisation relative to the aggregated market capitalisation of all the constituents of the index. This leads to one of an oft-cited critique of mainstream indices that they become “pro-cyclical”: namely, they allocate an increasing weight to the best performing stocks, and a decreasing weight to the worst performing stocks. This is true, but is coloured by your view as to which comes first, the stock performance chicken, or the index performance egg. Looking at concentration risk What is certainly true is that changes in company capitalisation can create significant stock concentrations in mainstream indices. For example, the top 5 holdings in the S&P 500 (Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet and Facebook) currently represent 21.6% of that index. The top 30 stocks represent 44.6%, and the top 100 stocks represent 69.9%. The remaining 400 stocks are a long tail of relatively smaller companies whose individual change in value will not materially impact the overall index performance. Fig.1. S&P500 Concentration  Size-bias is a choice not an obligation Index concentration, and related “size-bias”, the relative over-weighting of the largest companies, is however a choice, not an obligation for index investors. The existence of equal-weight indices enable a less concentrated exposure to the same components of an index. Whilst this solves the stock concentration risk, it creates a “Fear of Missing Out risk” when those large stocks are doing well. So, if choosing to use an equal-weighted index to reduce dependency on a concentrated index, communication is key. Reducing stock-specific risk may be welcome with end clients in theory, but clear messaging is required to explain that investment performance will not be comparable to the performance of funds (whether active or passive) using traditional capitalisation weighted benchmarks. End investors may feel they miss out when sentiment in the largest names is strong. But will be relieved when the reverse applies. On the basis that many investors are asymmetrically loss-averse, the more evenly distributed stock risk of an equal-weighted index could be something to consider. But only once any potential “Fear of Missing Out” has been discussed and addressed. Fig.2. S&P 500 vs S&P 500 Equal Weight, YTD Performance (USD terms); Fig.3. & FTSE 100 vs FTSE 100 Equal Weight, YTD Performance (GBP terms) Source: Elston Research, Bloomberg data, as at 18-Sep-20

Index selection is an active choice There’s no such thing as passive. Index investing is about adopting a systematic, rules-based approach to stock selection. There is an active choice to be made around methodology and index selection. If you don’t want to always hold the largest stocks, then don’t use a cap-weighted index. If you want to hold stocks based on other criteria – their earnings, their dividends, their style, or just equally weighted – there are plenty of other indices to choose from. It’s up to the index investor to make that active choice. Comments are closed.

|

ELSTON RESEARCHinsights inform solutions Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Company |

Solutions |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed