|

There’s no such thing as passive. Index investors make active decisions around asset allocation, index selection and index methodology. In this series of articles, I look at some of the key topics explored in my book “How to Invest With Exchange Traded Funds” that also underpin the portfolio design work Elston does for discretionary managers and financial advisers. If indices represent exposures, what is index investing and what are the ETFs that track them? Does using an index approach to investing mean you are a ‘passive investor’? I am not comfortable with the terms “active” and “passive”. A dynamically managed approach to asset allocation using index-tracking ETFs is not “passive”. The selection of an equal weighted index exposure over a cap weighted index is also an active decision. The design of an index methodology, requires active parameter choices. Hence our preference for the terms “index funds” and “non-index funds”. Indices represent asset classes. ETFs track indices. Index investing is the use of ETFs to construct and manage an investment portfolio. The evolution of indices The earliest equity index in the US is the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) which was created by Wall street Journal editor Charles Dow. The index launched on 26 May 1896, and is named after Dow and statistician Edward Jones and consists of 30 large publicly owned U.S. companies. It is a price-weighted index (meaning the prices of each security are totalled and divided by the number of each security to derive the index level). The earliest equity index in the UK is the FT30 Index (previously the FN Ordinary Index) was created by the Financial Times (previously the Financial News). The index launched on 1st July 1935 and consists of 30 large publicly owned UK companies. It is an equal-weighted index (meaning each of the 30 companies has an equal weight in the index). The most common equity indices now are the S&P500 (launched in 1957) for the US equity market and the FTSE100 (launched in 1984) for the UK Equity market. These are both market capitalisation-weighted indices (meaning the weight of each company within the index is proportionate to its market capitalisation (the share price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding)). According to the Index Industry Association, there are now approximately 3.28m indices, compared to only 43,192 public companies . This is primarily because of demand for highly customised versions of various indices used for benchmarking equities, bonds, commodities and derivatives. By comparison there are some 7,178 index-tracking ETPs globally. The reason why the number of indices is high is not because they are all trying to do something new, but because they are all doing something slightly different. For example, the S&P500 Index, the S&P500 (hedged to GBP) Index and the S&P 500 excluding Technology Index are all variants around the same core index. So the demand for indices is driven not only by investor demand for more specific and nuanced analysis of particular market exposures, but also for innovation from index providers. What makes a good index benchmark? For an index to be a robust benchmark, it has to meet certain criteria. Indices provided a combined price level (and return level) for a basket of securities for use as a reference, benchmark or investment strategy. Whilst a reference point is helpful, the use of indices as benchmarks enables informed comparison of fund or portfolio strategies. An index can be used as a benchmark so long as it has the following qualities (known as the “SAMURAI” test based on the mnemonic based on key benchmark characteristics in the CFA curriculum). It must be:

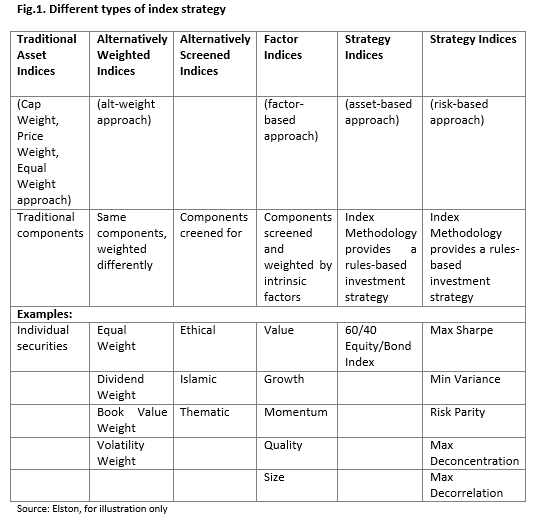

Alternative weighting schemes Whereas traditional equity indices took a price-weighted, equal-weighted or market capitalisation weighted approach, there are a growing number of indices that have alternative weighting schemes: given the underlying securities are the same, these variation of weighting scheme also contributes to the high number of indices relative to underlying securities. The advent of growing data and computing power means that indices have become more granular to reflect investors desire for more nuanced exposures and alternative weighting methodologies . Whether indices are driven by investor needs for isolated asset class exposures or by other preferences, there is a growing choice of building blocks for portfolio constructors.

Index investing Whilst indices have traditionally been used for performance measurement, if the Efficient Markets Hypothesis holds true, it makes sense to use an index as an investment strategy. A fund that matches the weightings of the securities within an index is an index-tracking fund. The use of single or multiple funds that track indices to construct and manage a portfolio is called “index investing”. We define index investing as 1) using indices (whether traditional cap-weighted or alternatively weighted) to represent the various exposures used within a strategic or tactical asset allocation framework, and 2) using index-tracking ETFs to achieve access to that exposure and/or asset allocation. The advantages of index investing with ETFs are:

As index investors we have a choice of tools at our disposal. The primary choice is to whether to use Index Funds or ETPs to get access to a specific index exposure. Index funds and ETPs Exchange Traded Products (ETPs) is the overarching term for investment products that are traded on an exchange and index-tracking. There are three main sub-sets:

Individual investors are most likely to come across physical Exchange Traded Funds and some Exchange Traded Commodities such as gold. Professional investors are most likely to use any or all types of ETPs. Both individual and professional investors alike are using ETPs for the same fundamental purposes: as a precise quantifiable building block with which to construct and manage a portfolio. Index investors have the choice of using index funds or ETFs. Index funds are bought or sold from the fund issuer, not on an exchange. ETFs are bought or sold on an exchange. For individual investors index funds may not be available at the same price point as for institutional investors. Furthermore, the range of index funds available to individual investors is much less diverse than ETFs. Trading index funds takes time (approximately 4-5 days to sell and settle, 4-5 days to purchase, so 8-10 days to switch), whereas ETFs can be bought on a same-day basis, and cash from sales settles 2 days after trading reducing unfunded round-trip times to 4 days for switches. If stock brokers allow it, they may allow purchases of one transaction to take place based on the sales proceeds of another transaction so long as they both settle on the same day. The ability to trade should not be seen as an incentive to trade, rather it enables the timely reaction to material changes in the market or economy. For professional investors, some index funds are cheaper than ETFs. Where asset allocation is stable and long-term, index funds may offer better value compared to ETFs. Where asset allocation is dynamic and there are substantial liquidity or time-sensitive implementation requirements, ETFs may offer better functionality than index funds. Professional investors can also evaluate the use of ETFs in place of index futures . For significant trade sizes, a complete cost-benefit analysis is required. The benefit of the ETF approach being that futures roll can be managed within an ETF, benefitting from economies of scale. For large investors, detailed comparison is required in order to evaluate the relative merits of each. The benefits of using ETFs There are considerable benefits of using ETFs when constructing and managing portfolios. Some of these benefits are summarised below:

Summary There’s no such thing as “passive investing”. There is such a thing as “index investing” and it means adopting a systematic (rules-based), diversified and transparent approach to access target asset class, screened, factor or strategy exposures in a straightforward, or very nuanced way. It is the systematisation of the investment process that enables competitive pricing, relative to active, “non-index” funds. This is a trend which has a long way to run before any “equilibrium” between index and active investing is reached. Most investors, automatically enrolled into a workplace pension scheme are index investors without knowing it. The “instutionalisation of retail” means that a similar investment approach is permeating into other channels such as discretionary managers, financial advisers, and self-directed investors. © Elston Consulting 2020 all rights reserved Comments are closed.

|

ELSTON RESEARCHinsights inform solutions Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Company |

Solutions |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed