|

What, one wonders, would Alfred Cowles III have made of the current “debate” about active and passive investing?

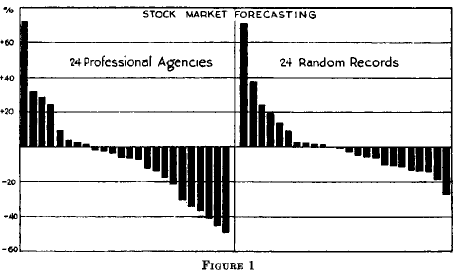

Cowles was born in 1891, the son of one of the founders of the Chicago Tribune. He became a successful businessman, but his true passions were economics and statistics. One question in particular exercised his mind — can the professionals predict the stock market? — and in 1927 he set out to find the answer. Over a period of four-and-a-half years, Cowles collected information on the equity investments made by the big financial institutions of the day as well as on the recommendations of market forecasters in the media. There were no index funds at the time, but he compared the performance of both the professionals and the forecasters with the returns delivered by the Dow Jones Industrial Average. His findings were published in 1933 in the journal Econometrica, in a paper entitled Can Stock Market Forecasters Forecast? The financial institutions, he found, produced returns that were 1.20% a year worse than the DJIA; the media forecasters trailed the index by a massive 4% a year. “A review of these tests,” he concluded, “indicates that the most successful records are little, if any, better than what might be expected to result from pure chance.” 11 years later, in 1944, Cowles published a larger study, based on nearly 7,000 market forecasts over a period of more than 15 years years. In it he concluded once again that there was no evidence to support the ability of professional forecasters to predict future market movements. What is so extraordinary about Alfred Cowles’ work, and the techniques he used, is how ahead of his time he was. Cowles was the first person to measure the performance of market forecasters empirically. Even among students of academic finance, the common perception is that it wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the value of active money management was seriously called into question, most famously by Paul Samuelson and Charles Ellis. In fact it was Cowles, more than 30 years previously, who first provided data to show that it was, to use Ellis’ phrase, a loser’s game. So why wasn’t Cowles’ research more widely known about? Why did it take until 1975 for the first retail index fund to be launched? And why is active management still the dominant mode of investing even now, in 2018? There are probably many reasons. The power of the industry lobby and the large advertising budgets at the disposal of the major fund houses have undoubtedly played a part, as has the growth of the financial media. But it was Alfred Cowles himself who put his finger on arguably the biggest factor behind the enduring appeal of active management. Late in life, Cowles was interviewed about his research into market forecasters. In Peter Bernstein’s 1992 book, Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Wall Street, he is quoted as saying this: “Even if I did my negative surveys every five years, or others continued them when I’m gone, it wouldn’t matter. People are still going to subscribe to these services. They want to believe that somebody really knows. A world in which nobody really knows can be frightening.” Cowles’ prediction has proved to be spot on. Both active management and market forecasting are far bigger industries than they were when he died in 1984. Investors, it seems, still want to believe that the market can be beaten, despite all the evidence that no more fund managers succeed in doing it than is consistent with random chance. Comments are closed.

|

ELSTON RESEARCHinsights inform solutions Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Company |

Solutions |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed